History of Medical Illustration through the World

History of Medical Illustration through the World

As a medical illustrator, studying the work of other artists is an important part of my free time, I would like to offer some perspective and, for what it is worth, an admittedly subjective but well-researched chronology for those interested in the best medical illustrators in history, and in different regions arund the world. I realize there are going to be enormous gaps. Please feel free to write to me and to comment below, and to add your favorites so my perspective can be the most well-rounded possible.

Where did Medical Illustration Begin?

Medical Illustration in Early Medieval Europe

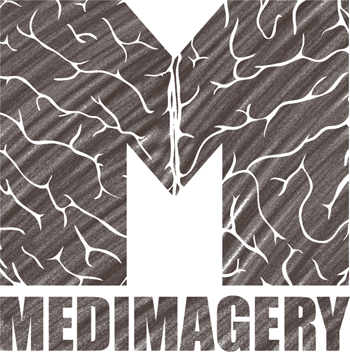

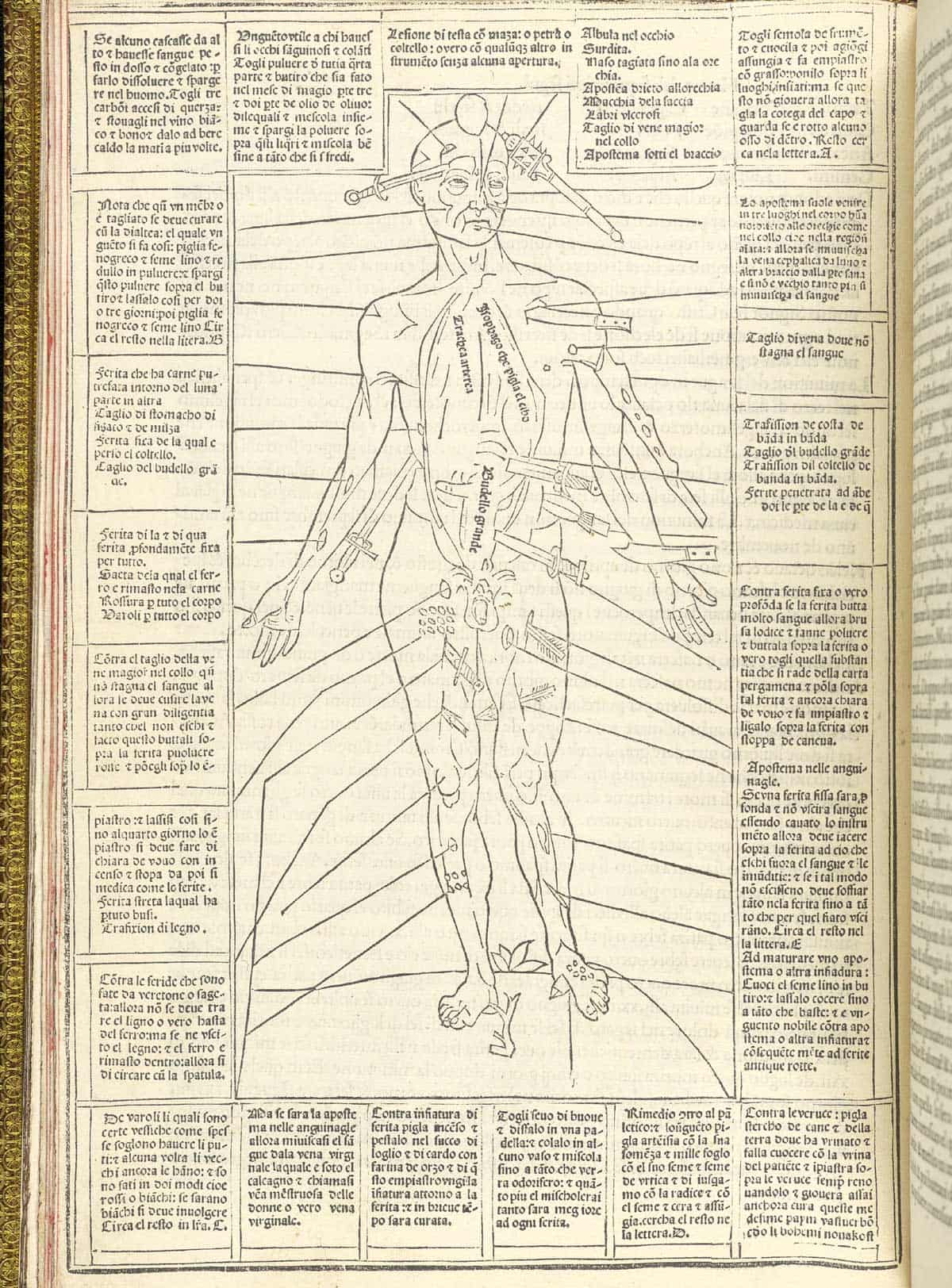

Fasciculus Medicinae | The First Printed Medical Illustrations in Europe

Wound Man

Anatomy Illustration in Ancient China

Unlike Western anatomy, the spleen is a very important organ in the traditional Chinese medical system. … The spleen and stomach in traditional Chinese medicine represent the digestive system.

Late Medieval and Early Modern Medicine

As the Islamic world became increasingly fragmented, the patronage and accompanying prestige and security enjoyed by the leading physicians declined. Spain was lost, European crusaders made repeated invasions into the central lands, and in the 13th century Mongol invasions from the east disrupted life. The Mamluk rulers in Egypt managed to hold off the Mongol invasions, and it is no doubt for that reason that the medical community there remained active longer than elsewhere, with the exception of Safavid Iran.

The hospitals were dependent upon charitable endowments for their maintenance, and with time these funds became insufficient to support them, or, not infrequently, the lands supporting the endowment were confiscated. Consequently, the hospitals tended to deteriorate and eventually fall into disuse, except for a few such as the Nuri hospital in Damascus which continued to operate as a hospital until the end of the 19th century. With the expansion of the population, the remaining hospitals and dispensaries proved inadequate. Nonetheless, the learned medical community remained quite productive through the 14th century, particularly in Syria and Egypt. Within two more centuries, however, vitality and creativity had disappeared, the medical literature had stultified, and the practice of medicine deteriorated to the point where it no longer represented the medieval tradition at its best. In the latter half of the 16th century, Islamic medicine then became receptive to some of the ideas, techniques, and drug therapies developing in Europe.

Early modern European influence can first be seen in the earliest Islamic treatise on syphilis. This was written by `Imad al-Din Mas`ud Shirazi, a physician at the hospital in Mashhad in northeast Iran. In his Persian treatise on syphilis written in 1569 (977 H), he followed the European practice of advocating for its treatment the use of China Root (Chub-chini), the rhizome of an Old World species of Smilax found in eastern Asia. This new drug for treating a new disease was rapidly incorporated into Arabic medical writings. For example, Da’ud al-Antaki, a Syrian physician who died in 1599 (1008 H), included a similar description of syphilis and China Root in his Arabic medical encyclopedia. Da’ud al-Antaki also relied heavily upon medieval Islamic writers and earlier Greek sources, for which he learned Greek so as to study them directly.

In the 17th century, early modern European medical theory had an impact upon Islamic medicine through the writings of the Paracelsians, followers of Paracelsus (d. 1541), whose `chemical medicine’ employed mineral acids, inorganic salts, and alchemical procedures in the production of remedies. Sali ibn Nasr ibn Sallum, a physician born in Aleppo, Syria, and later court physician in Istanbul to the Ottoman ruler Mehmet IV (ruled 1648-1687/1058-1099 H) was greatly influenced by these writings.

Ibn Sallum incorporated into his book The Culmination of Perfection in the Treatment of the Human Body (Ghayat al-itqan fi tadbir badan al-insan ) translations of several Latin Paracelsian writings, such as those by Oswald Croll (d. 1609), professor of medicine at the University of Marburg, and Daniel Sennert (d. 1637), professor of medicine at Wittenberg. Therapy was primarily a drug therapy, with diseases explained in terms of salt, quicksilver and sulphur rather than the Galenic theory of the balance of humors. Many of the medicaments required distillation processes and plants that were indigenous to the New World, such as guaiacum and sarsaparilla. The treatise not only reflects the new chemical medicine of the European Paracelsians, but also described for the first time in Arabic a number of `new’ diseases, such as scurvy, chlorosis, anaemia, the English sweat (a type of influenza), and plica polonica (an eastern European epidemic of matted and crusted hair caused by infestation with lice).

Occasionally bloodletting and cautery figures, clearly derivative from similar illustrations in medieval European manuscripts, are found in some Islamic manuscripts of about the 17th century or later. By the 17th century it appears that Vesalius’s Latin treatise The Fabric of the Human Body (De humani corporis fabrica) printed in 1542-3 was also known in the Safavid and Ottoman empires, for a number of preserved ink sketches of the 17th through 19th century indicate familiarity with illustrations from the Fabrica.

In the 17th century not only did early modern European medical ideas filter into the Middle East, but Europeans became interested in learning of the medical practices then current in the Islamic world. One example is Joseph Labrosse, who was born in Toulouse in 1636 and entered the order of Discalced Carmelites, taking the name of Fr. Angelus of St. Joseph. In 1662 he went to Rome and studied Arabic for two years, and then in 1664 went to Isfahan and studied Persian. While in Iran, he used medicine as a means of propagating Christianity and in the process read many Arabic and Persian books on medicine and “visited the houses of the learned people of Isfahan and paid hundreds of visits to the shops of the druggists, the pharmacists, and the chemists.

After Labrosse returned to France, he published his Pharmacopoea Persica and a few years later a Gazophylacium linguae persarum,which was a dictionary of Persian words with Italian, Latin and French definitions, with much attention paid to medical terms. The Pharmacopoea Persica ex idiomate Persica in Latinum conversa, published in Paris in 1681, consists of a Latin translation made by Father Angelus de Sanctu Josepho (Joseph Labrosse) of a Persian book on compound remedies by Muzaffar ibn Muhammad al-Husayni (d. 1556/663 H), with additional comments by Labrosse.

In the middle of the 18th century the plague befell Istanbul, and the traditional Islamic medicine seemed to do little to combat it. Consequently, the Ottoman sultan Mustafa III ordered a Turkish translation to be made of two treatises by Hermann Boerhaave (d. 1738), a Dutch medical reformer and advocate of bedside instruction. The Turkish versions were completed in 1768 by the court physician Subhi-Zade `Abd al-`Aziz with the assistance of the Imperial Austrian interpreter Thomas von Herbert. Subhi-Zade attempted not only to translate Boerhaave’s ideas but to reconcile and harmonize them with traditional Islamic medicine.

It was not until the 19th century that profound changes occurred in the teaching of medicine in the Near East. In 1825 Antoine-Barthelemy Clot was appointed surgeon-in-chief to the Egyptian army. Clot had been a physician at Montpellier prior to coming to Egypt, and by 1828 he established a medical school near Cairo at which French, Italian and German professors taught. In 1850 a military medical school, the Dar al-Funun, was founded in Tehran in Iran, where instruction was given in French by professors from Austria and Italy. A number of European medical texts were translated into Persian at this school.

The most recent Islamic manuscript in the collections of the National Library of Medicine is an important document for the nature of medical care in one region of the Middle East just prior to the establishment of medical schools on a European model. It is an autograph copy of a Miscellany on the Art of Medicine (Khalitah fi sina`at al-tibb) completed on the 6th of January 1814 (14 Muharram 1229 H) by a North African physician Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Salawi. Following 48 years of experience, he discussed the diseases most common in North Africa in his day, warning against the use of some drugs approved by older authorities and occasionally advocating the methods used by European doctors.

Then, as now, however, aspects of traditional medieval Islamic medicine continued to coexist alongside the modern European medicine. In the late 19th century treatises of Ibn Sina, al-Majusi, and Ibn al-Baytar, among others, were printed at the Bulaq press in Cairo because they continued to represent a vital tradition, which the Yunani medical colleges of Pakistan and India are continuing, at least in part, to maintain today.

https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/islamic_medical/islamic_14.html

Renaissance Period Medical Illustrations

15th Century Leonardo Da Vinci

DaVinci’s drawings are perhaps the most extraordinary and well-drawn medical illustrations ever created. His observational skills and three dimensional skills were ahead of his time by hundreds of years. Most of what he knew and understood about anatomy came from his own observations. I often imagine what he could have done if he were born in modern times, able to take medical knowledge for granted, but living in a world where the MRI and CT scan capture the three-dimensional inner anatomical world so thoroughly. Would he be taking medicine for granted and move on to less well understood topics? Maybe also, less drawing and painting in favor of a newer exploration and curious edge? I have explored this great artist in more detail on another page. Please see my article on Leonardo Da Vinci for a full range of illustrations and a description of his techniques and his life.

William Harvey

A century after Da Vinci, William Harvey was an English physician and anatomist who lived 1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657 discovered that blood circulates from the heart and back to the heart, and noted that blood turns blue in the lack of oxygen. He overthrew Galen’s ideas about blood, and the tradition that blood was produced in the liver. Harvey was not well-received by the medical establishment of the day, who preferred Galen’s theories.

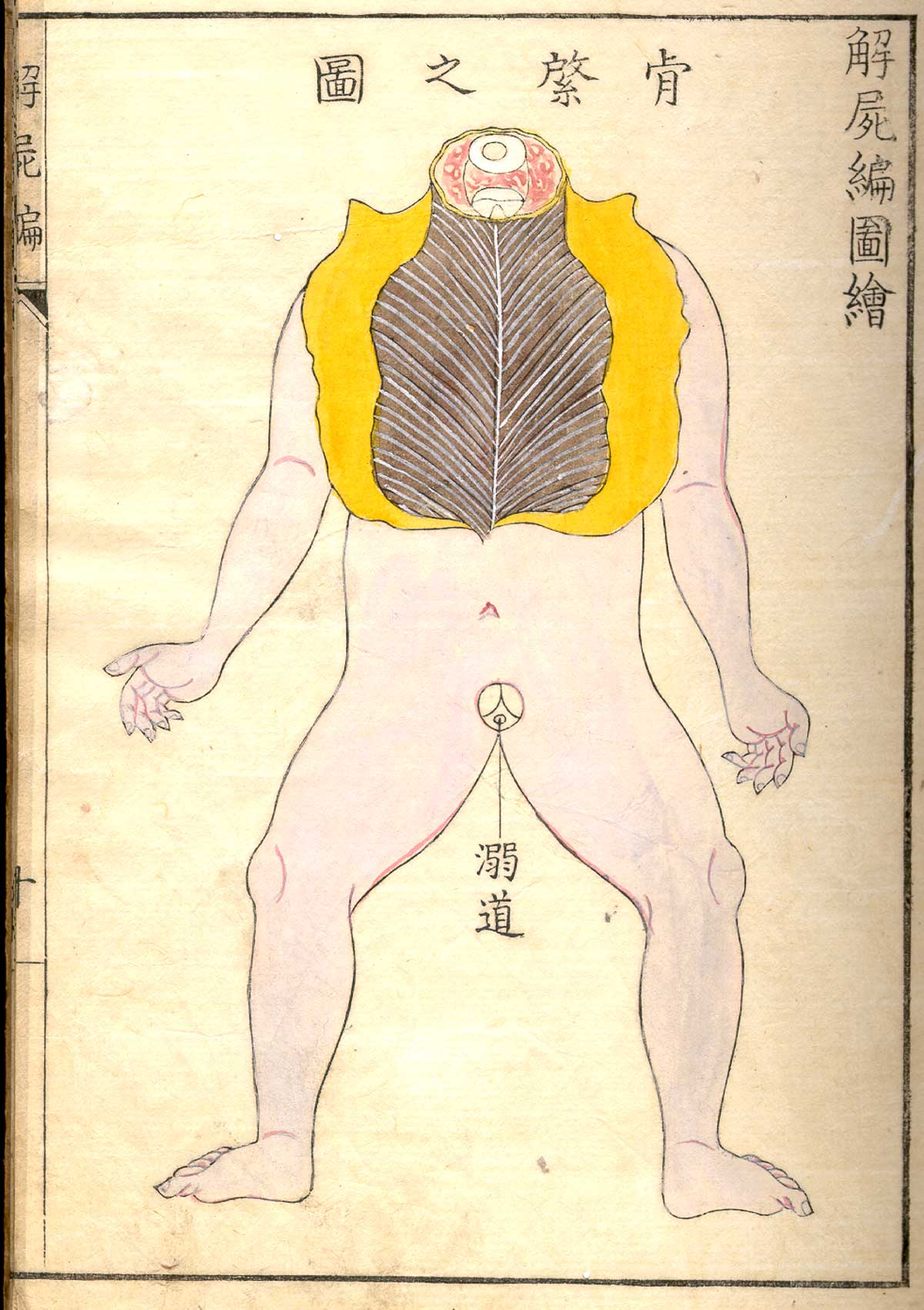

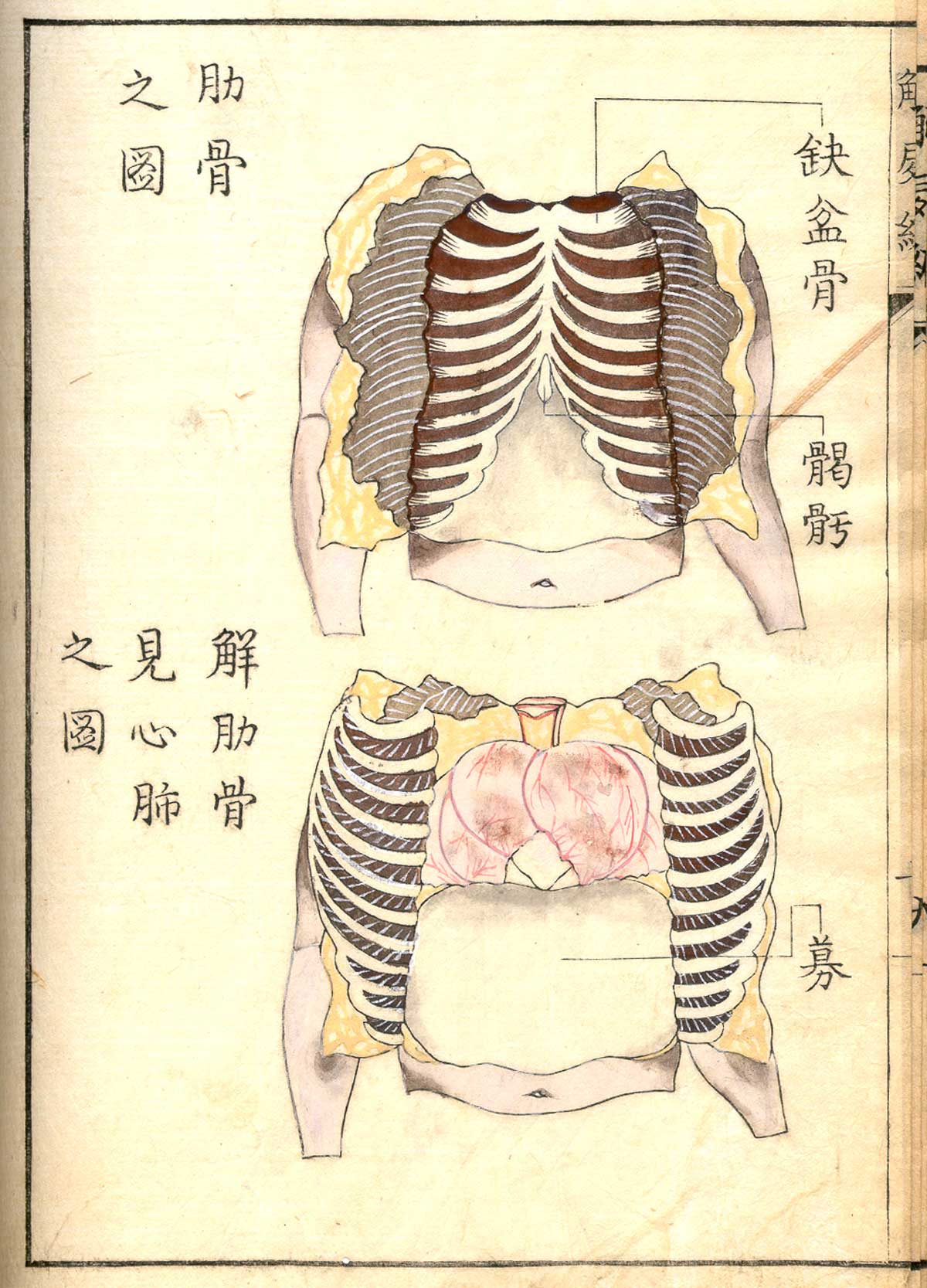

Anatomical illustrations from Edo-period Japan

Here is a selection of old anatomical illustrations that provide a unique perspective on the evolution of medical knowledge in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868).

Pregnancy illustrations, circa 1860

These pregnancy illustrations are from a copy of Ishinhō, the oldest existing medical book in Japan. Originally written by Yasuyori Tanba in 982 A.D., the 30-volume work describes a variety of diseases and their treatment. Much of the knowledge presented in the book originated from China. The illustrations shown here are from a copy of the book that dates to about 1860.

* * * * *

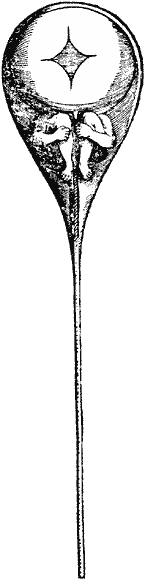

Anatomical illustrations, late 17th century [+]

These illustrations are from a late 17th-century document based on the work of Majima Seigan, a 14th-century monk-turned-doctor. According to legend, Seigan had a powerful dream one night that the Buddha would bless him with knowledge to heal eye diseases. The following morning, next to a Buddha statue at the temple, Seigan found a mysterious book packed with medical information. The book allegedly enabled Seigan to become a great eye doctor, and his work contributed greatly to the development of ophthalmology in Japan in the 16th and 17th centuries.

* * * * *

Trepanning instruments, circa 1790 [+]

These illustrations are from a book on European medicine introduced to Japan via the Dutch trading post at Nagasaki. Pictured here are various trepanning tools used to bore holes in the skull as a form of medical treatment.

Trepanning instruments, circa 1790 [+]

The book was written by Kōgyū Yoshio, a top official interpreter of Dutch who became a noted medical practitioner and made significant contributions to the development of Western medicine in Japan.

* * * * *

Trepanning instruments, 1769 [+]

These illustrations of trepanning instruments appeared in an earlier book on the subject.

* * * * *

Anatomical illustrations (artist/date unknown) [+]

These anatomical illustrations are based on those found in Pinax Microcosmographicus, a book by German anatomist Johann Remmelin (1583-1632) that entered Japan via the Dutch trading post at Nagasaki.

* * * * *

Human skeleton, 1732

These illustrations — created in 1732 for an article published in 1741 by an ophthalmologist in Kyōto named Toshuku Negoro — show the skeletal remains of two criminals that had been burned at the stake.

Human skeleton, 1732

This document is thought to have inspired physician Tōyō Yamawaki to conduct Japan’s first recorded human dissection.

* * * * *

Japan’s first recorded human dissection, 1754

These illustrations are from a 1754 edition of a book entitled Zōzu, which documented the first human dissection in Japan, performed by Tōyō Yamawaki in 1750. Although human dissection had previously been prohibited in Japan, authorities granted Yamawaki permission to cut up the body of an executed criminal in the name of science.

Illustration from 1759 edition of Zōzu

The actual carving was done by a hired assistant, as it was still considered taboo for certain classes of people to handle human remains.

* * * * *

Japan’s second human dissection, 1758 // First human female dissection, 1759

In 1758, a student of Tōyō Yamawaki’s named Kōan Kuriyama performed Japan’s second human dissection (see illustration on left). The following year, Kuriyama produced a written record of Japan’s first dissection of a human female (see illustration on right). In addition to providing Japan with its first real peek at the female anatomy, this dissection was the first in which the carving was performed by a doctor. In previous dissections, the cutting work was done by hired assistants due to taboos associated with handling human remains.

* * * * *

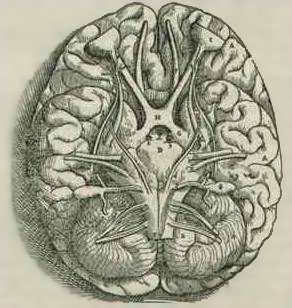

Kaishihen (Dissection Notes), 1772

Japan’s fifth human dissection — and the first to examine the human brain — was documented in a 1772 book by Shinnin Kawaguchi, entitled Kaishihen (Dissection Notes). The dissection was performed in 1770 on two cadavers and a head received from an execution ground in Kyōto.

Kaishihen (Dissection Notes), 1772

Kaishihen (Dissection Notes), 1772

Kaishihen (Dissection Notes), 1772

* * * * *

Tōmon Yamawaki, son of Tōyō Yamawaki, followed in his father’s footsteps and performed three human dissections.

Female dissection, 1774

He conducted his first one in 1771 on the body of a 34-year-old female executed criminal. The document, entitled Gyokusai Zōzu, was published in 1774.

Female dissection, 1774

Female dissection, 1774

Female dissection, 1774

* * * * *

Female dissection, 1800

These illustrations are from a book by Bunken Kagami (1755-1819) that documents the dissection of a body belonging to a female criminal executed in 1800.

Female dissection, 1800

* * * * *

Human anatomy (date unknown)

This anatomical illustration is from the book Kanshin Biyō, by Bunken Kagami.

Human anatomy (date unknown)

In this image, a sheet of transparent paper showing the outline of the body is placed over the anatomical illustration.

* * * * *

Seyakuin Kainan Taizōzu (circa 1798)

These illustrations are from the book entitled Seyakuin Kainan Taizōzu, which documents the dissection of a 34-year-old criminal executed in 1798. The dissection team included the physicians Kanzen Mikumo, Ranshū Yoshimura, and Genshun Koishi.

Seyakuin Kainan Taizōzu (circa 1798)

Seyakuin Kainan Taizōzu (circa 1798)

* * * * *

Dissection, 1783 [+]

This illustration is from a book by Genshun Koishi on the dissection of a 40-year-old male criminal executed in Kyōto in 1783.

* * * * *

Breast cancer treatment, 1809

These illustrations are from an 1809 book documenting various surgeries performed by Seishū Hanaoka for the treatment of breast cancer. The illustrations here depict the treatment for a 60-year-old female patient.

* * * * *

Bandage instructions from two medical encyclopedias, 1813

* * * * *

Yōka Hiroku (Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1847

These illustrations are from the 1847 book Yōka Hiroku (Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths) by surgeon Sōken Honma (1804-1872).

Yōka Hiroku (Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1847

* * * * *

The following illustrations are from the 1859 book Zoku Yōka Hiroku (Sequel to Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), an 1859 book by Sei Kawamata that presented the teachings of surgeon Sōken Honma.

Zoku Yōka Hiroku (Sequel to Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1859

Zoku Yōka Hiroku (Sequel to Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1859

Zoku Yōka Hiroku (Sequel to Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1859

Zoku Yōka Hiroku (Sequel to Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1859

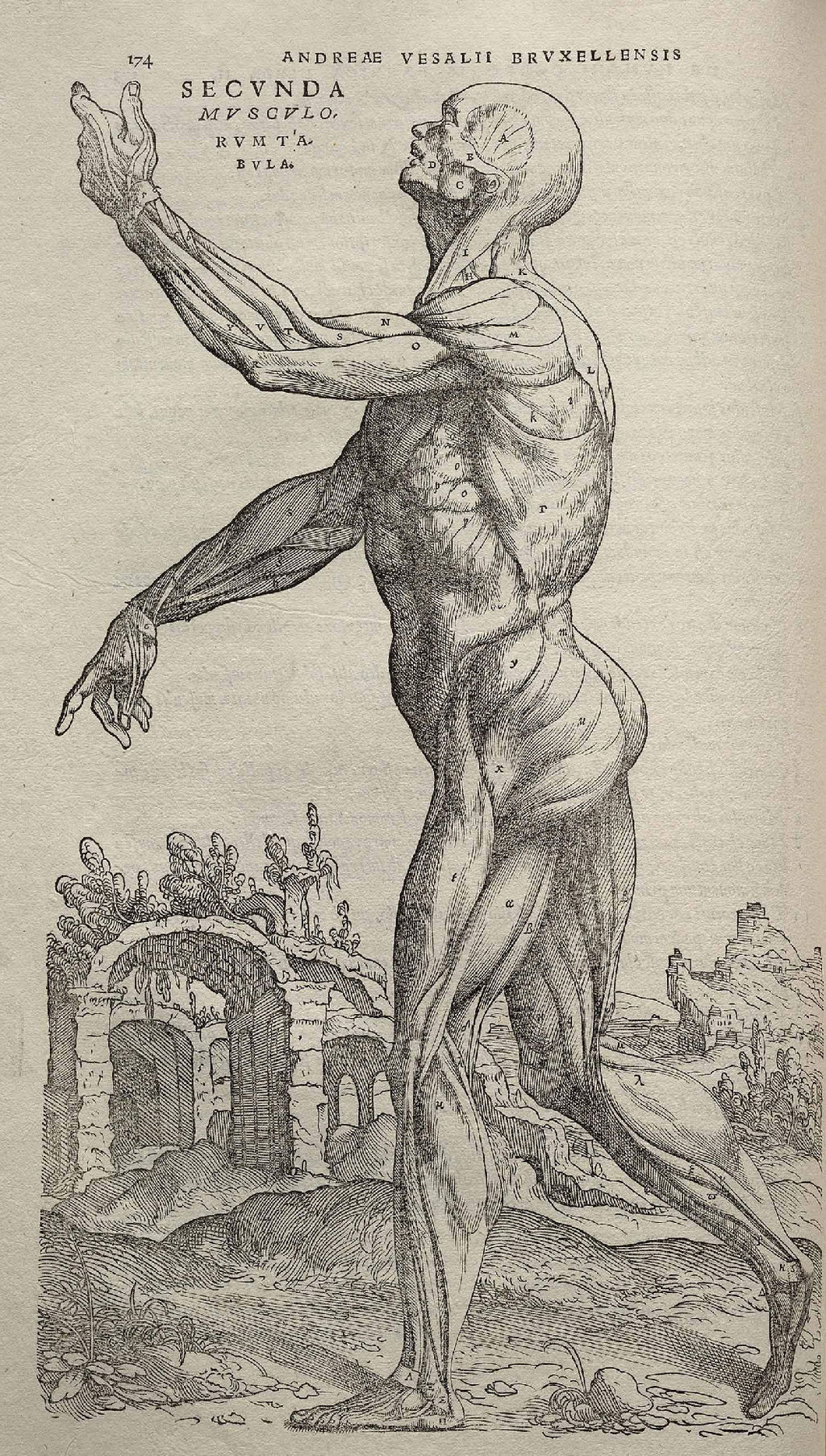

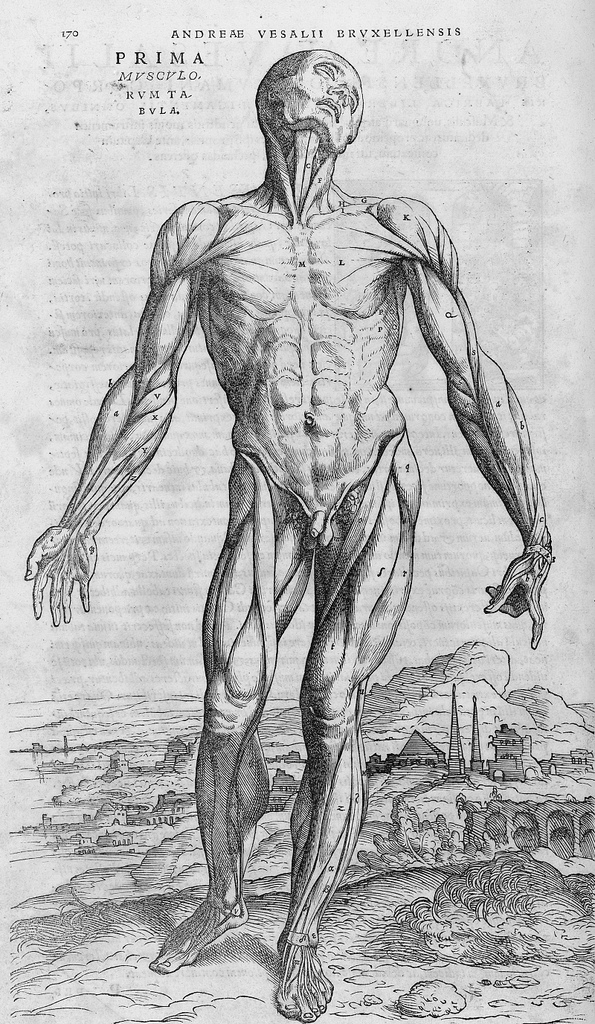

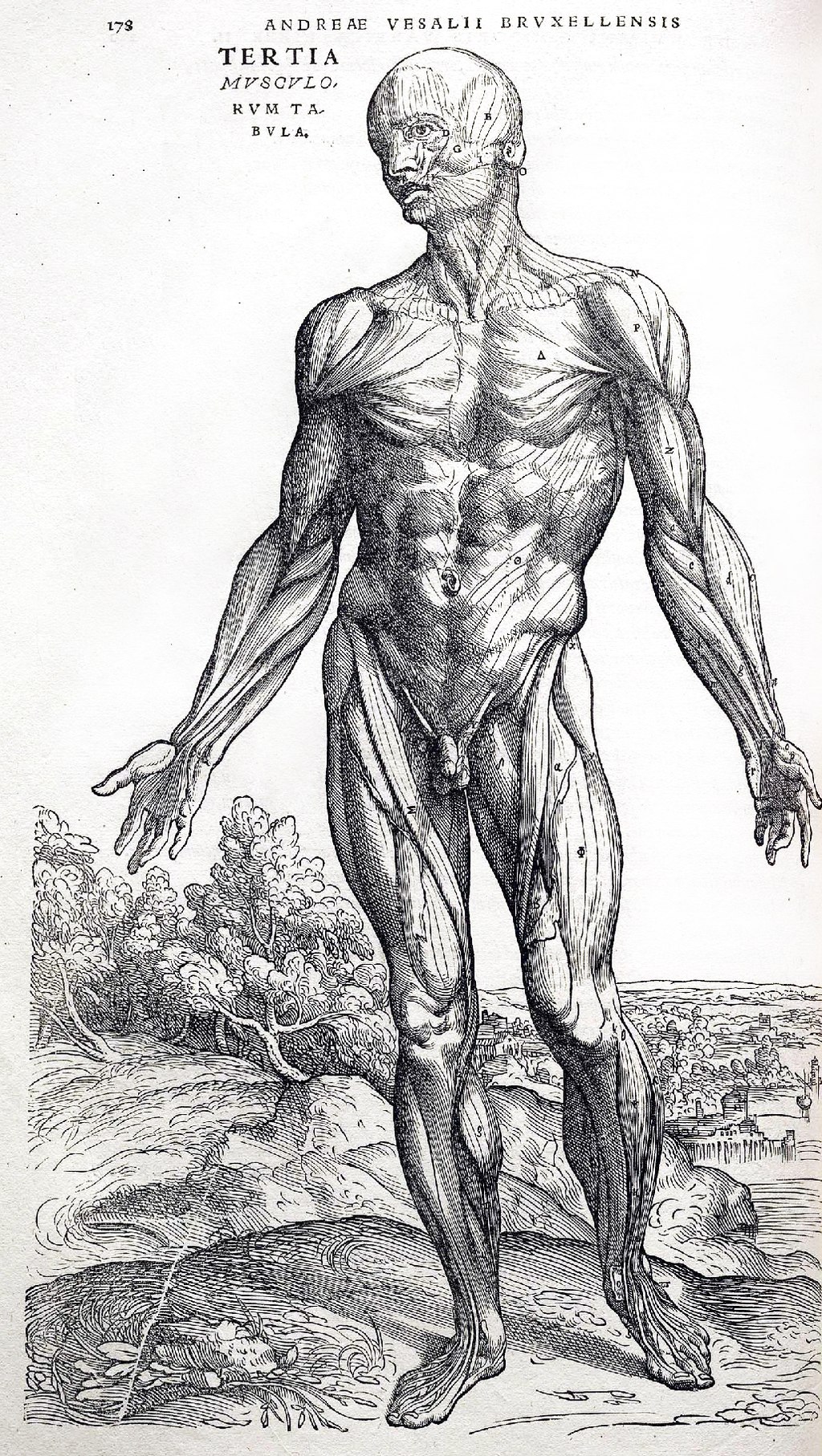

Medical Illustration in the 16th Century

Andreas Vesalius 31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564)

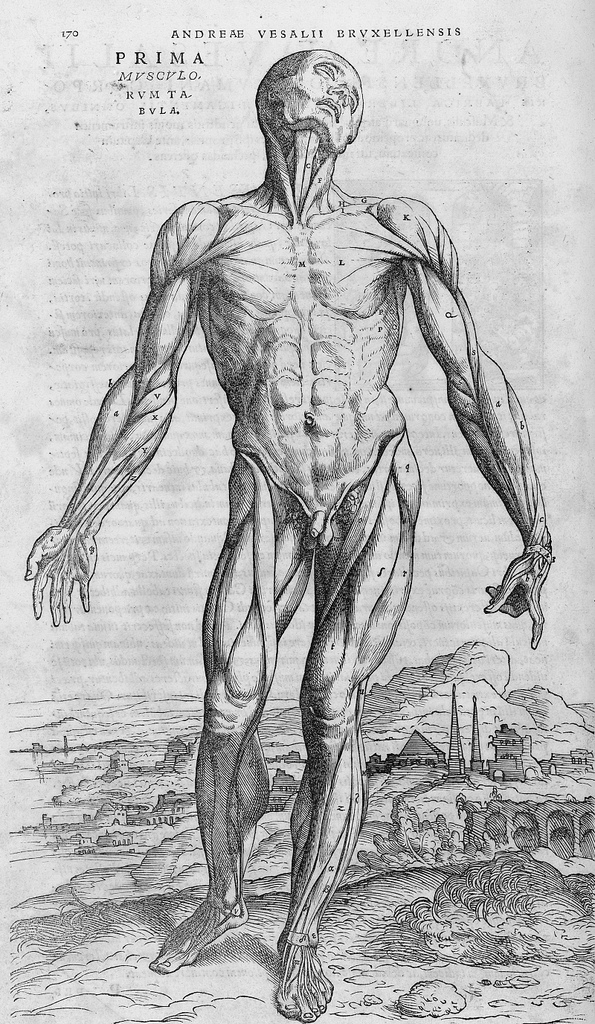

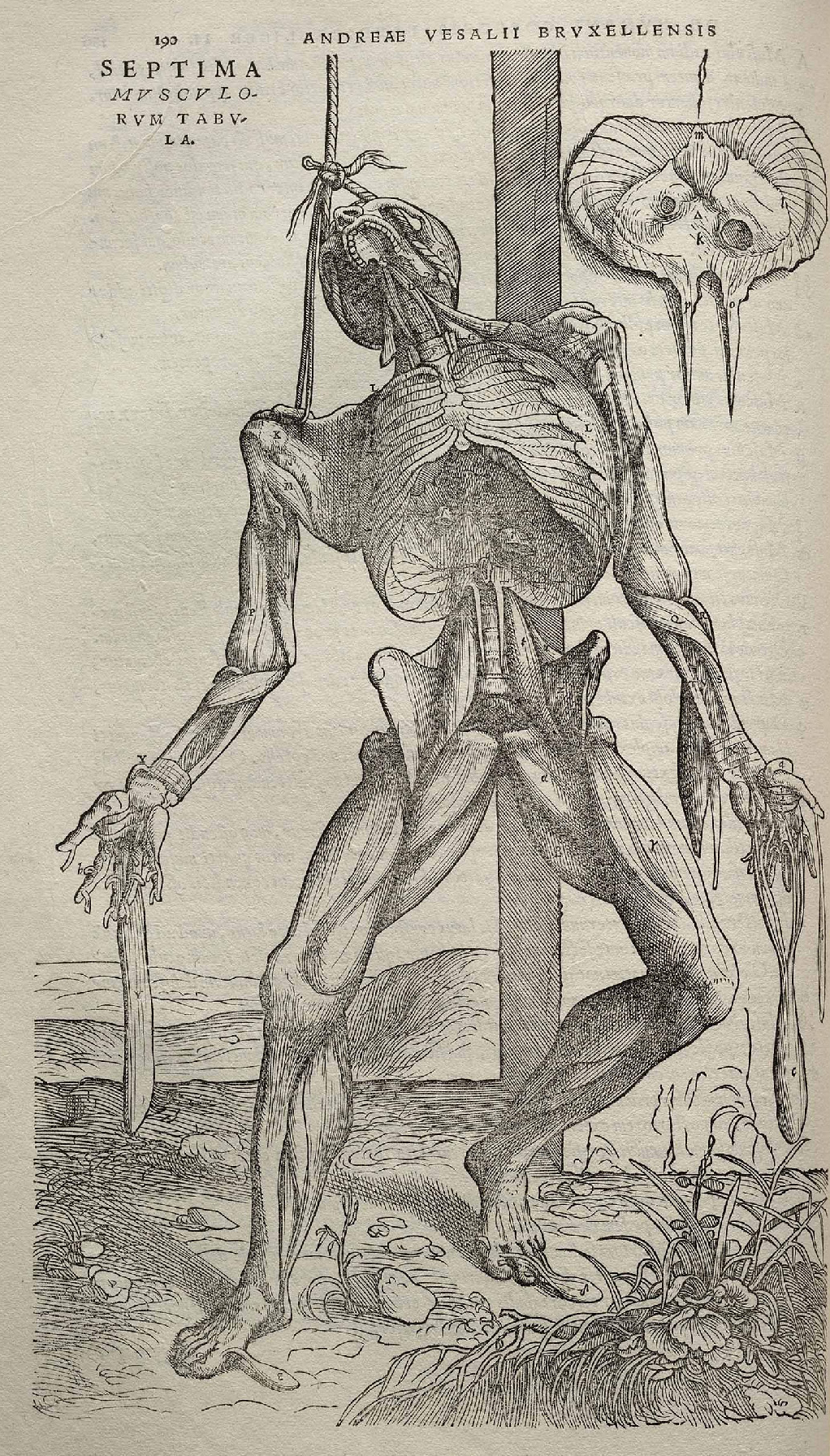

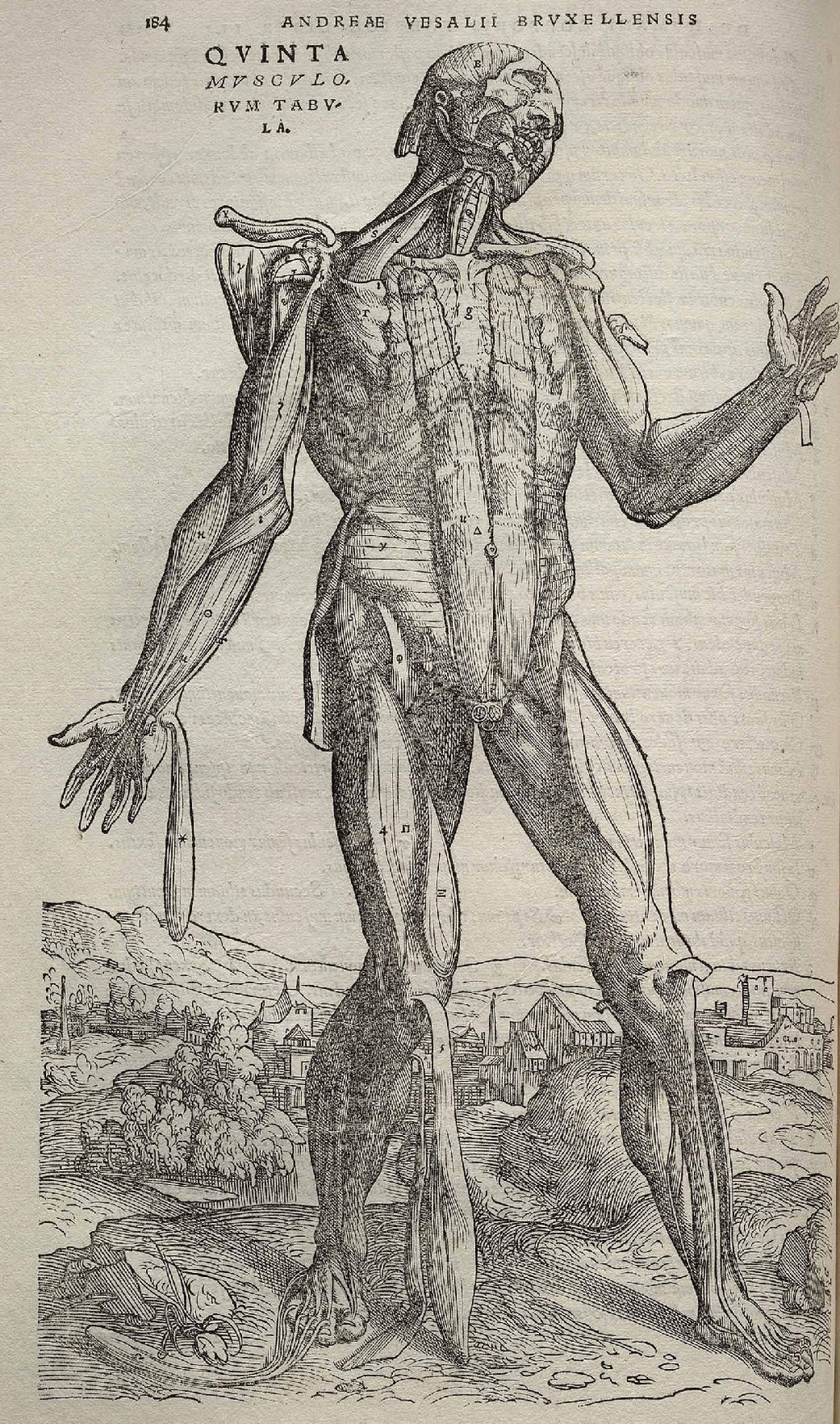

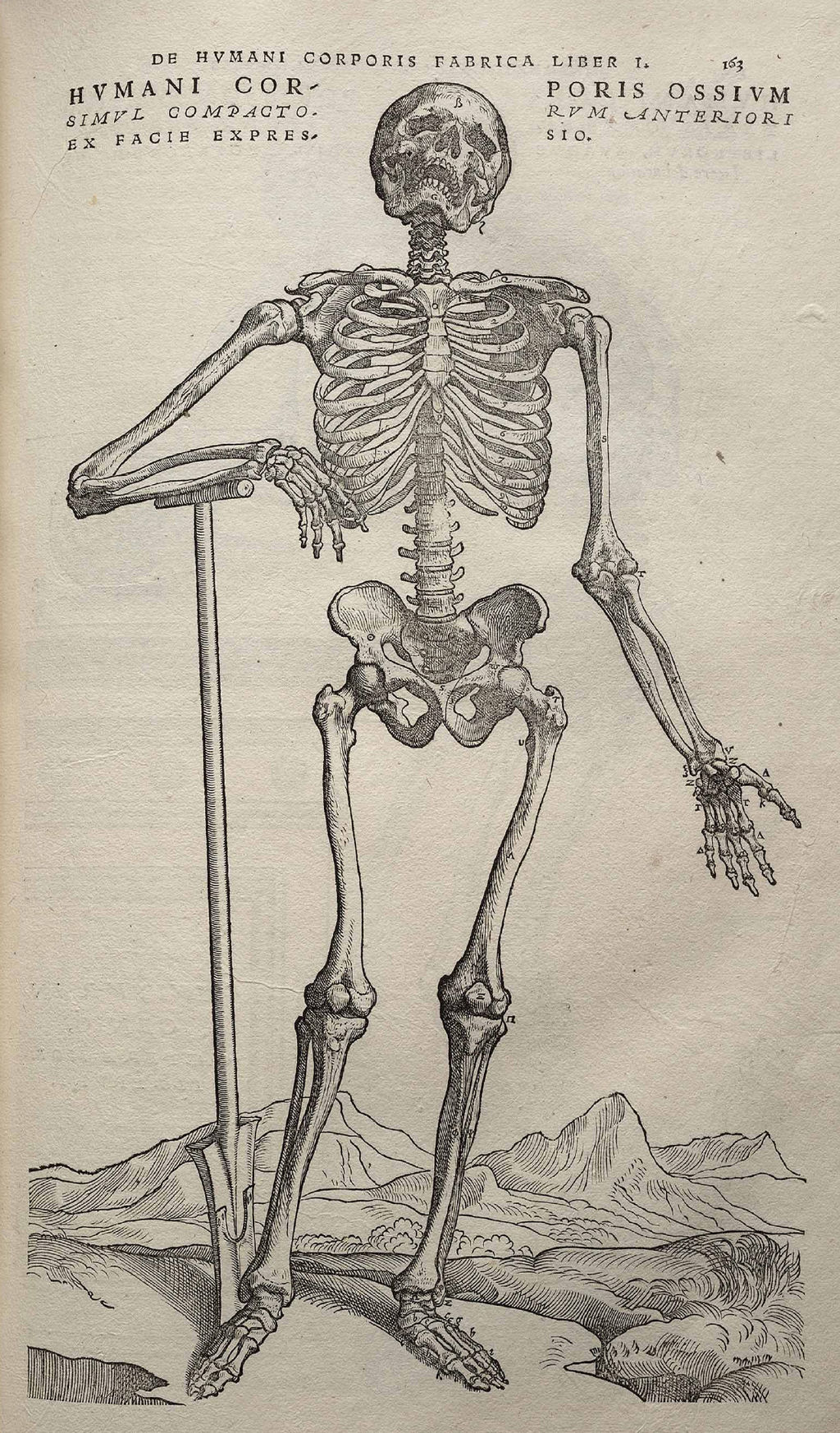

Andreas Vesalius (/vɪˈseɪliəs/;[1] 31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564) was a 16th-century Flemish anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body). Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy. He was born in Brussels, which was then part of the Habsburg Netherlands. He was professor at the University of Padua and later became Imperial physician at the court of Emperor Charles V.

Andreas Vesalius is the Latinized form of the Dutch Andries van Wesel. It was a common practice among European scholars in his time to Latinize their names. His name is also given as Andrea Vesalius, André Vésale, Andrea Vesalio, Andreas Vesal, André Vesalio and Andre Vesalepo.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andreas_Vesalius

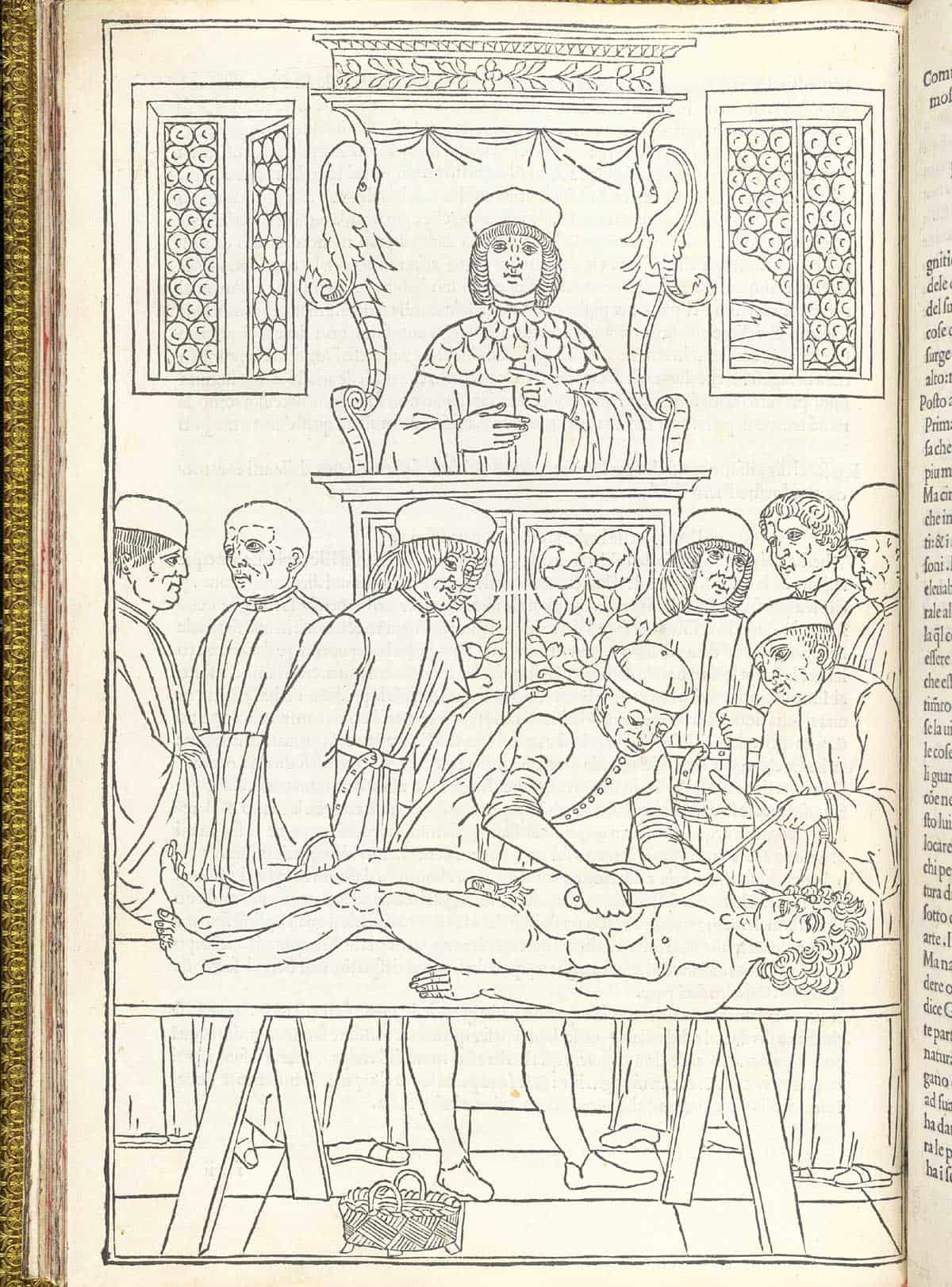

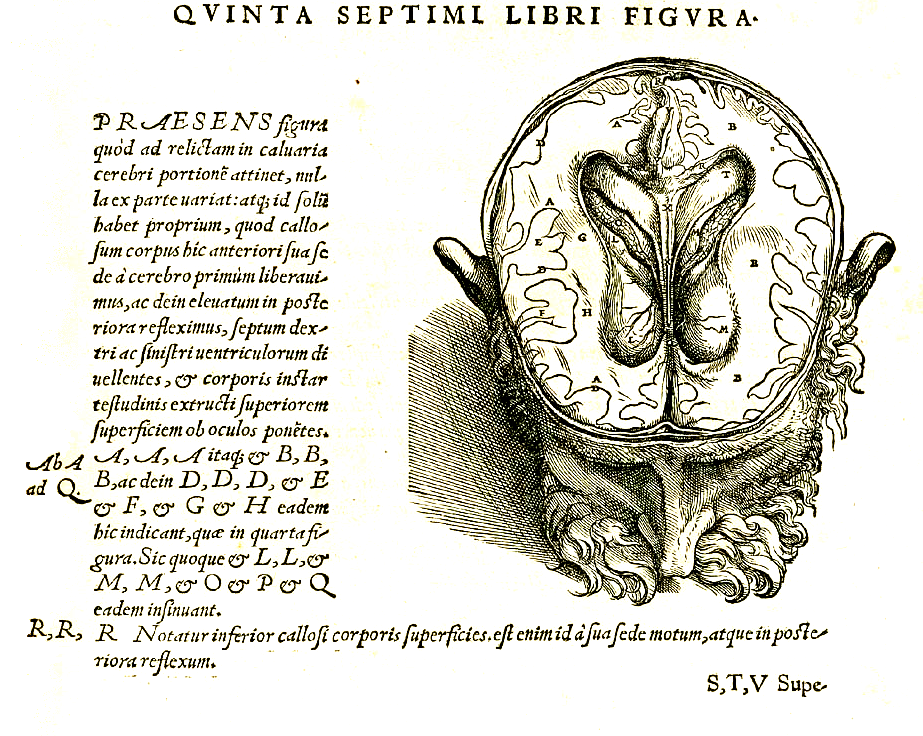

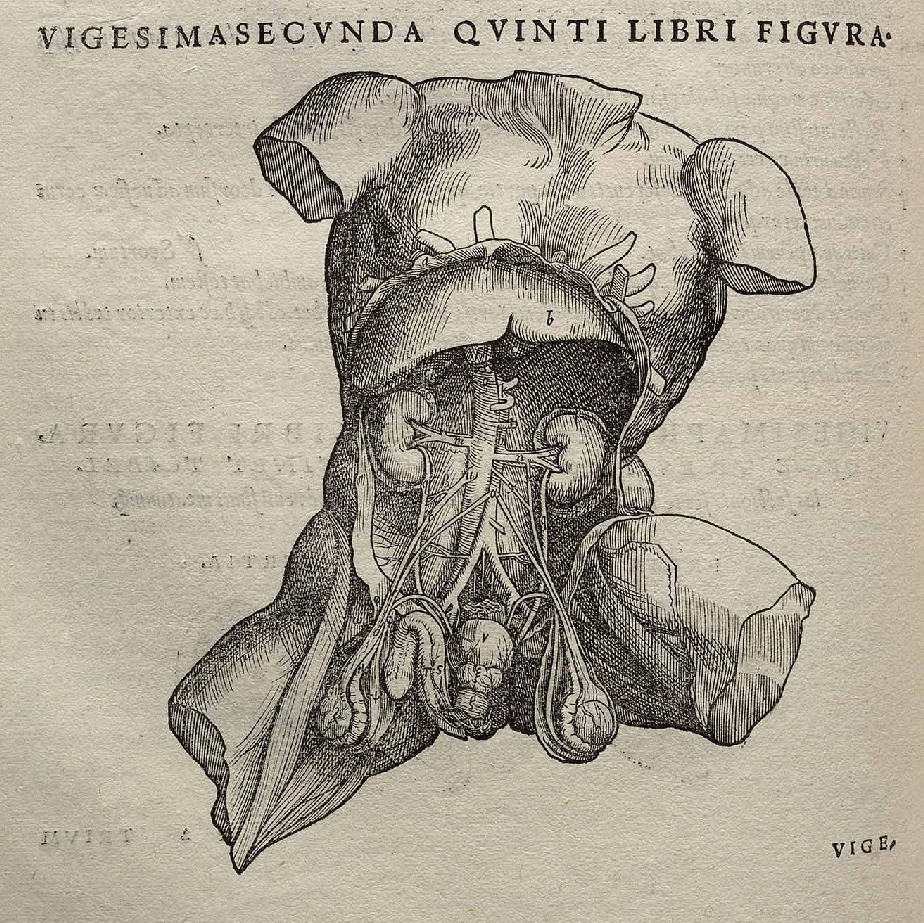

De humani corporis fabrica

The Fabrica is known for its highly detailed illustrations of human dissections, often in allegorical poses.

De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Latin for “On the fabric of the human body in seven books”) is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history of anatomy over the long-dominant work of Galen, and presented itself as such.

The collection of books is based on his Paduan lectures, during which he deviated from common practice by dissecting a corpse to illustrate what he was discussing. Dissections had previously been performed by a barber surgeon under the direction of a doctor of medicine, who was not expected to perform manual labour. Vesalius’s magnum opus presents a careful examination of the organs and the complete structure of the human body. This would not have been possible without the many advances that had been made during the Renaissance, including artistic developments in literal visual representation and the technical development of printing with refined woodcut engravings. Because of these developments and his careful, immediate involvement, Vesalius was able to produce illustrations superior to any produced previously.

Vesalius Fabrica fronticepiece

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_humani_corporis_fabrica

Medical Illustrators in the 20th Century

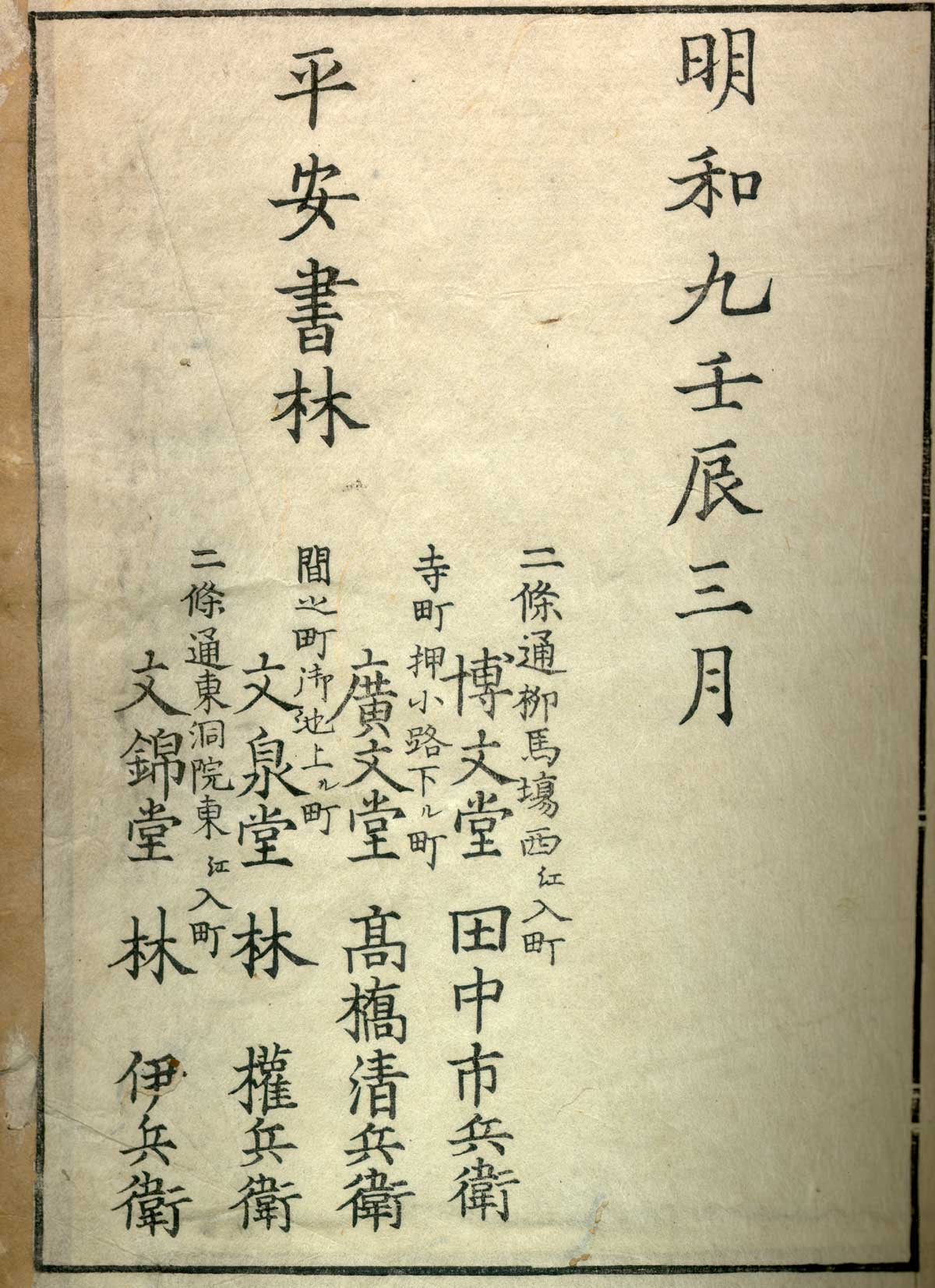

Medical lllustration in 18th Century Japan

Publication Information: Heian [Kyoto]: Hakubundō Tanaka Ichibe, Meiwa 9 [1772]. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

Publication Information: Heian [Kyoto]: Hakubundō Tanaka Ichibe, Meiwa 9 [1772]. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

Publication Information: Heian [Kyoto]: Hakubundō Tanaka Ichibe, Meiwa 9 [1772]. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

Max Brödel

Max Brödel (June 8, 1870 – October 26, 1941) was a medical illustrator. Born in Leipzig, Germany,

Frank H. Netter

When I think about my own career as a medical illustrator, based upon the comments I receive when I tell people about my career, Frank Netter is the name mentioned most often by the people I have met, mores than Leonardo Da Vinci. Frank Henry Netter was a New York City native, born 25 April 1906 and died 17 September 1991. As an American surgeon and artist with a colorful style, most people remember the very personal nature of his clinical art and anatomical drawings. His interest in art was primary to his interest in medicine, which seems natural and typical to me as my own love of medical illustration grew from a love of observation and drawing, to a love of anatomy. Da Vinci’s life took he same pattern. He began his career with a scholarship to the National Academy of Design, upon which he began drawing for the Saturday Evening Post and The New York Times. The talented Netter was not winning approval from his parents, and so he decided to pursue medicine. He attended the City College of New York and then went on to complete medical school at New York University, with a surgical internship at Bellevue Hospital. Drawing was a daily practice for Netter throughout his life. Drawing medicine became second nature, having received a medical education. Pharmaceutical companies began to seek Netter to represent the techniques they were developing for clinical practice. According to Wikipedia, “Soon after a misunderstanding wherein Netter asked for $1,500 for a series of 5 pictures and an advertising manager agreed to and paid $1,500 each – $7,500 for the series – Netter gave up the practice of medicine.” Good for Netter!!

_____________________________________

Laura Maaske, MSc.BMC.

Biomedical Communicator

Medical Illustrator

Medical Legal Illustrator

Medical Animator

Health App Developer