Best Medical & Scientific Illustrators in History Series: Maria Sibylla Merian

Hailed the “co-founder of entomology“

Maria Sibylla Merian is renowned because of

her skills at close direct observation,

accurate documentation,

insights about insect life cycles, and

her ability to transport her viewers to this world

Maria Sibylla Merian was among the first scientists to

- Observe insects directly

- Document their life cycle, foods, and habitats

- Reveal the process of metamorphosis in different insect species

- Confirm that insects do not spontaneously generate

- Collect and document vast numbers of insects from around the world

- Simply to show great interest in insects

- Draw and paint with the skill to transport her viewer into her own world of reasoned understanding and imaginative expression

- Fight social and gender norms of her time

- Focus on the interaction of organisms with environment made her among the first voices in the emerging field of ecology

- Illustrated in a fairly natural or realistic setting which set a new standard for scientific illustration objectives. Other scientific illustrators of her day had biases about the superiority of humans, or embellished nature to make it more visually appealing.

Maria Sibylla Merian was leading in all these areas at a time when insects were deeply detested by Europeans, and when women were not given respect or access to scientific and geographical exploration.

The Year 1647. BIRTH & CHILDHOOD

The Year 1665. NUREMBERG. MARRIAGE & CHILDREN

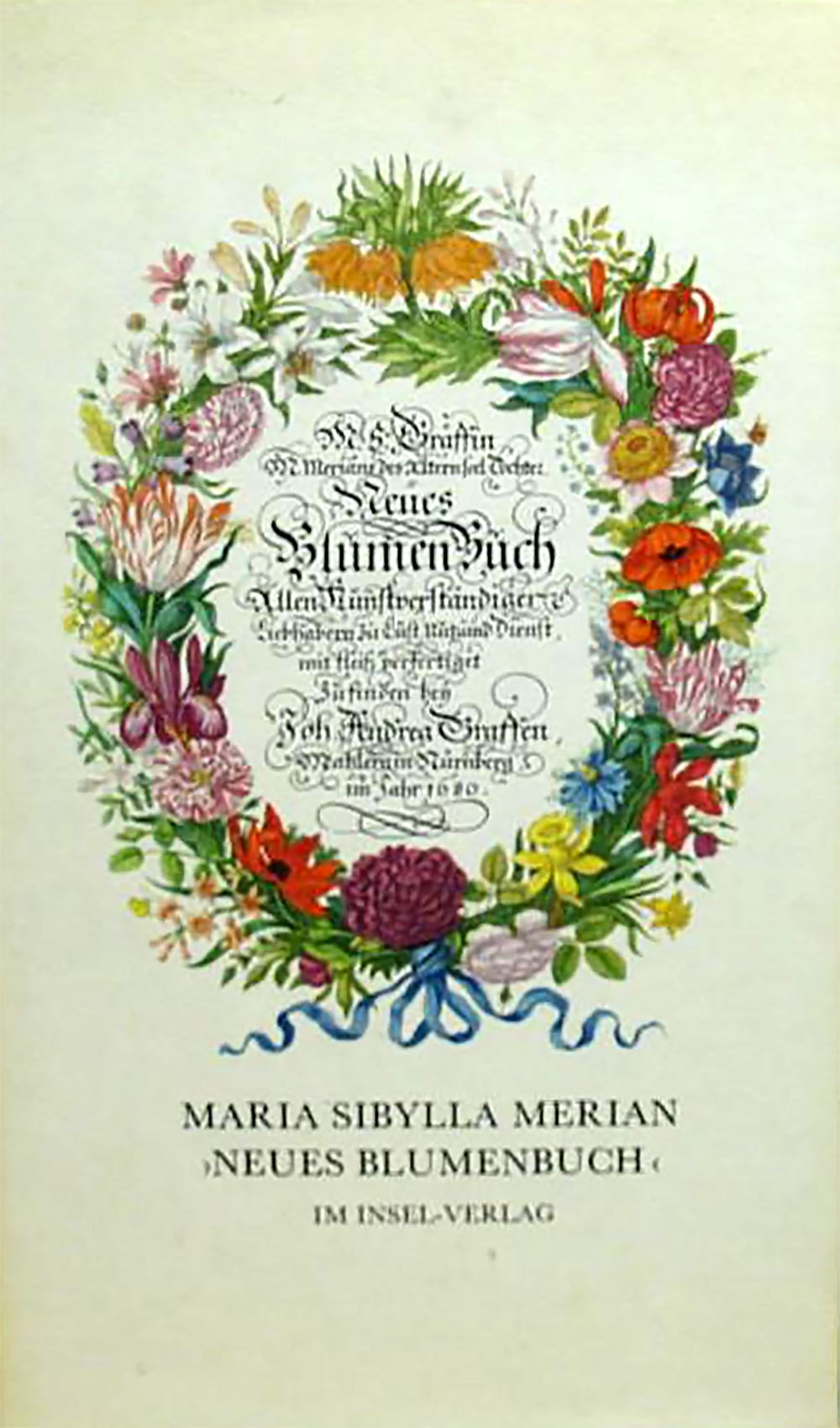

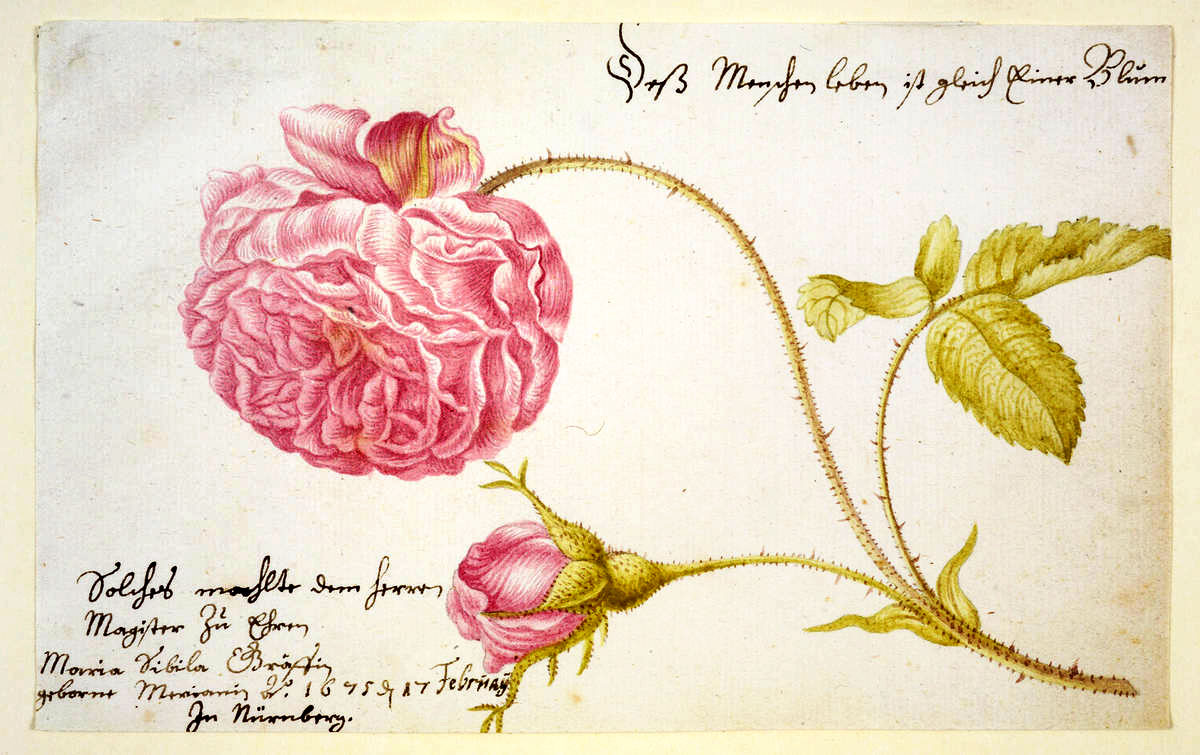

The Year 1675. FIRST BOOK, in THREE VOLUMES: FLOWERS

- Blumenbuch. Volume 1. 1675

- Blumenbuch. Volume 2. 1677

- Neues Blumenbuch. Volume 3. 1680

When she was 28 years old, she published her first book of naturalist illustrations, called “Neues Blumenbuch” or, “New Flowers Book”. However beautiful and accurately represented these depictions were for a scientific community in need of visual reference (no photography at that time) for classification of references, the scientific community of the time largely ignored Maria’s work because it wasn’t published in Latin, the formal language of science.

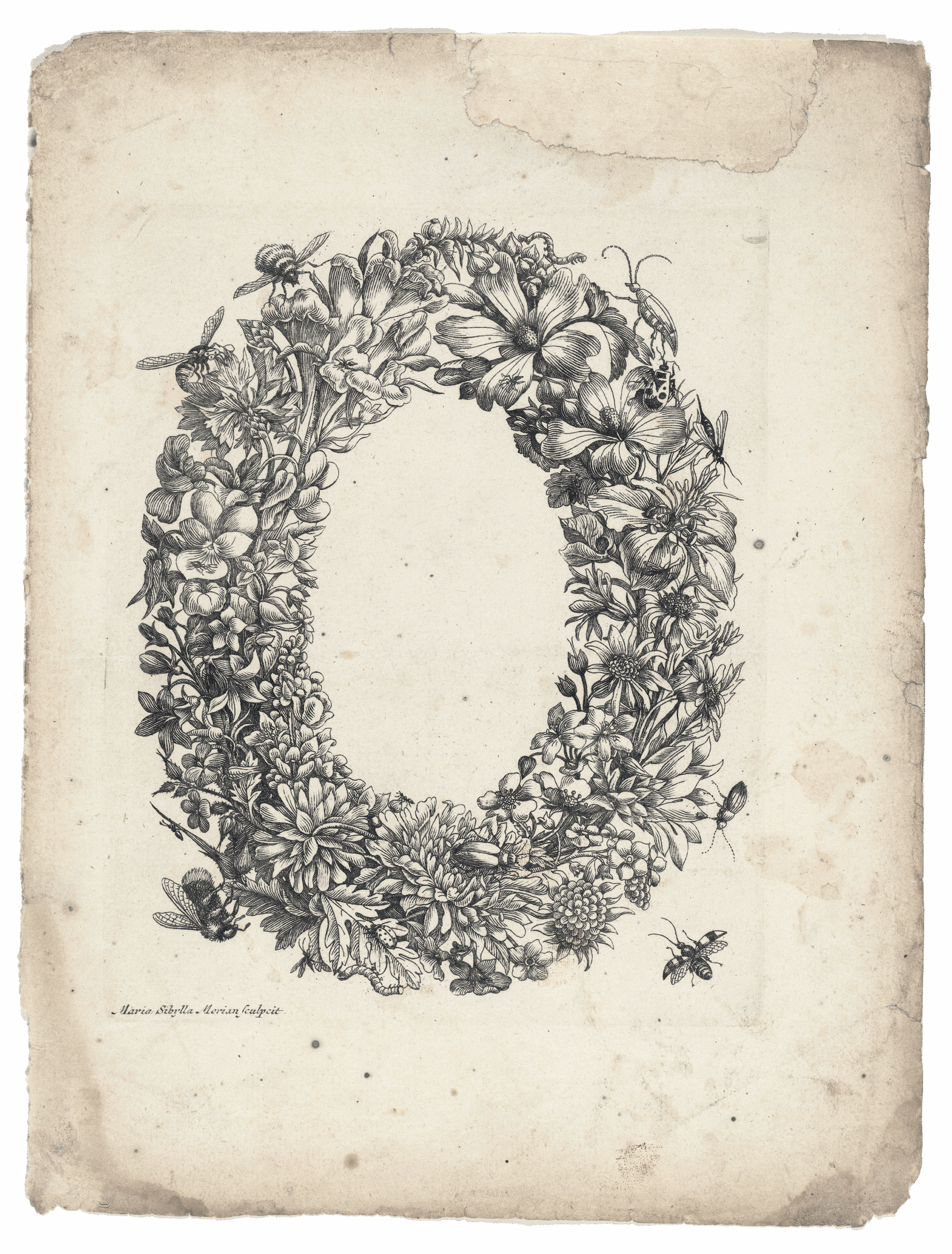

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1700

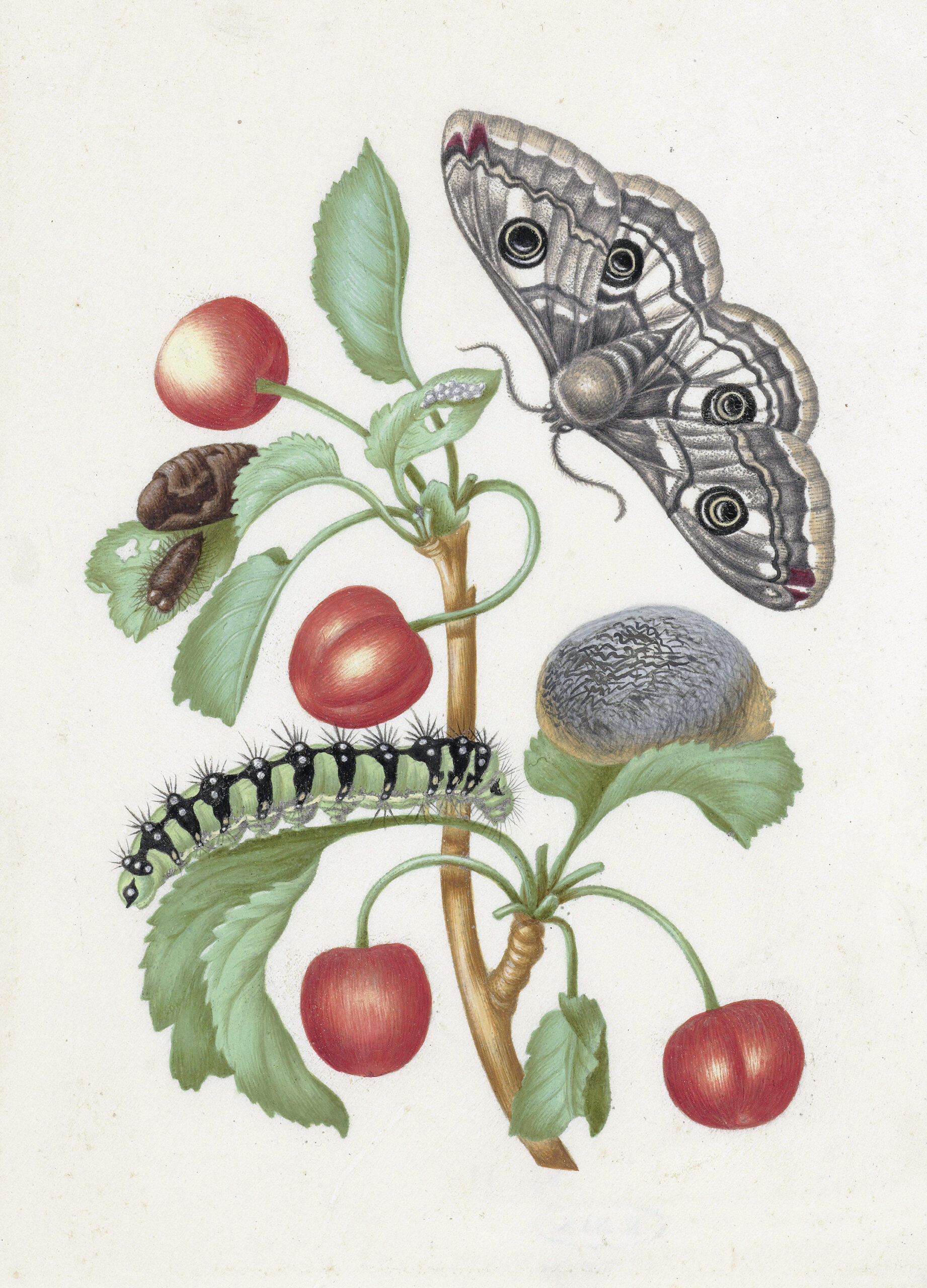

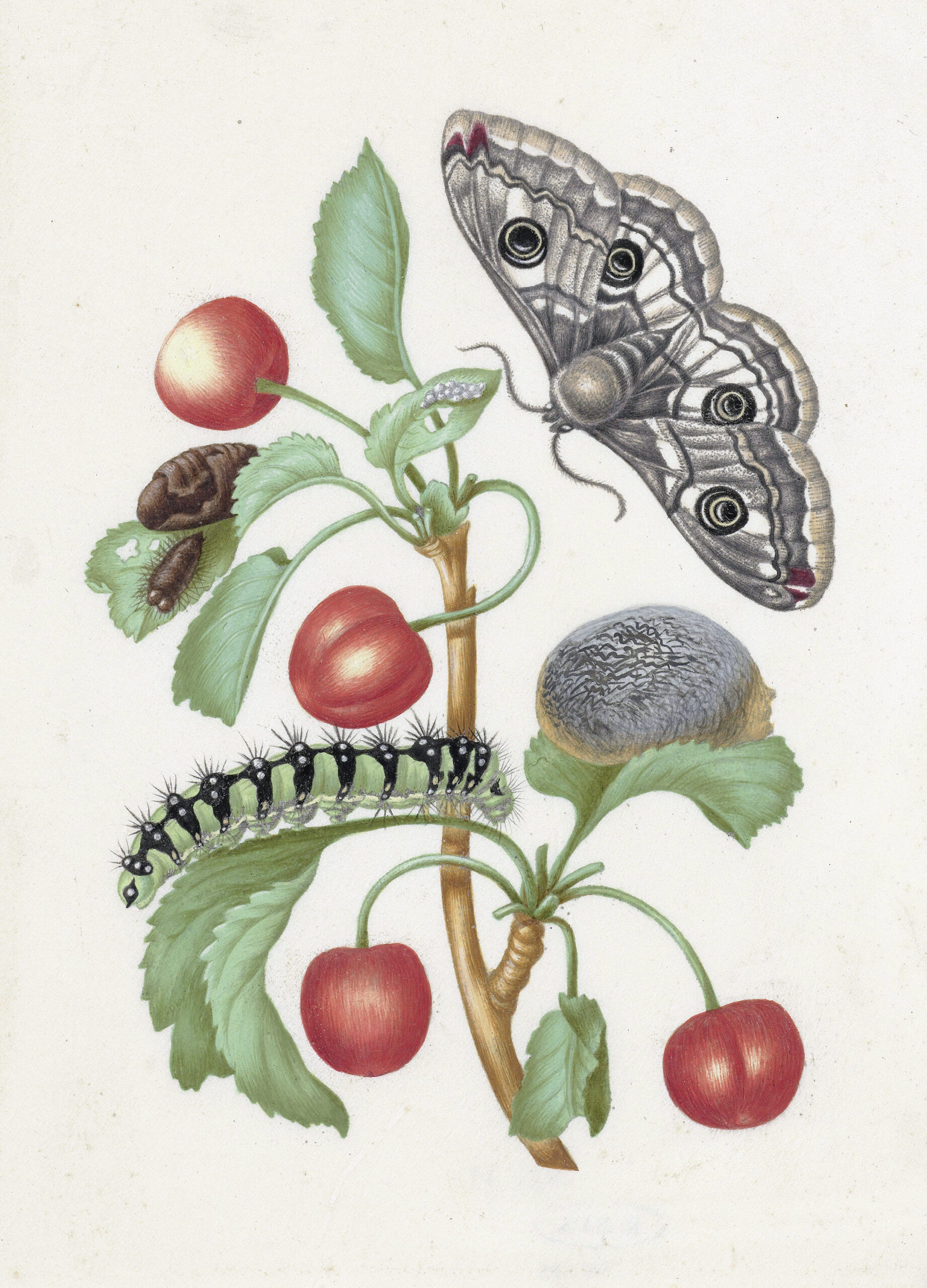

Previous: Tulip, two Branches of Myrtle and two ShellsNext: Branch of West Indian Cherry with Achilles Morpho Butterfly

Floral Wreath with Insects, 1700 — Maria Sibylla Merian,

Dimentions: height: 17.5 cm, width: 13.8 cm

Movements:The Enlightenment

Mediums:Engraving

Collection:Rijksmuseum

Subjects:FlowersInsects

Image Rights:Public Domain

The book is a big success with its audience because it is an inspiration to embroiderers, and it develops into a three volume series by1679. Maria painted watercolor on vellum

It is still not understood at this time by most scientists

how the life cycle of the butterfly and moth worked.

Maria was driven

to observe and understand

the cycle for herself.

Because she is the first entomologist

to reveal this,

she is known as among

the greatest entomologists in history.

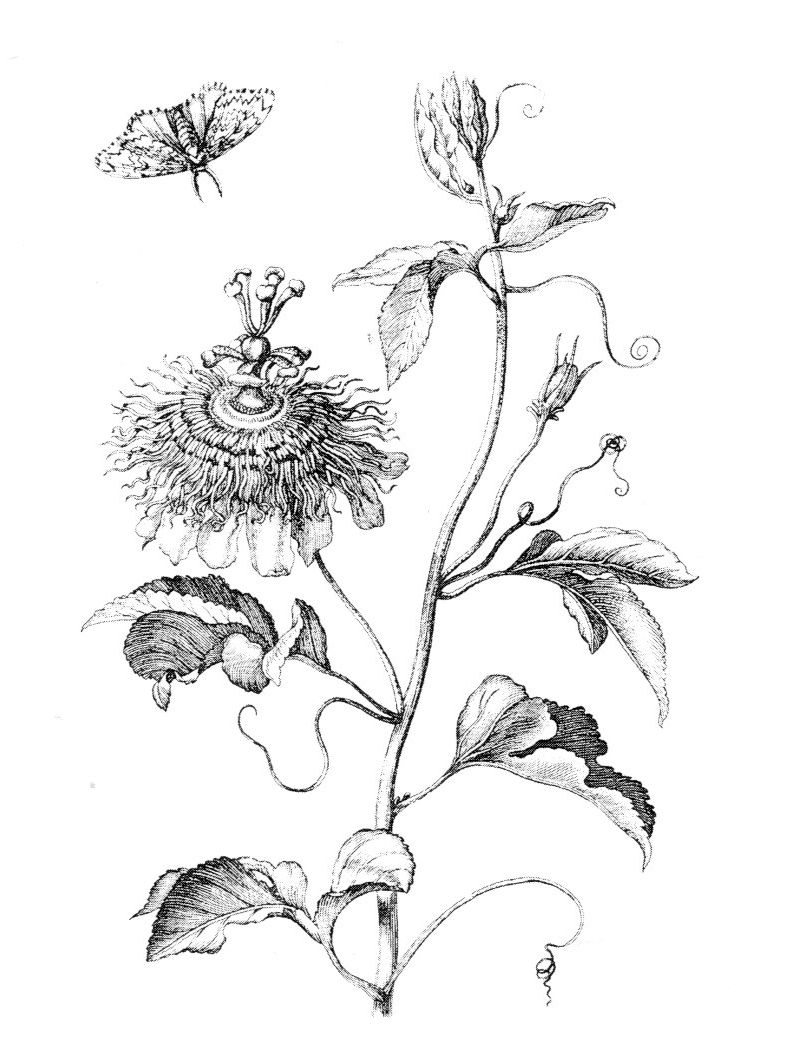

The Year 1679. DER RAUPEN WUNDERBARE VERWANDLUNG UND SONDERBARE BLUMENNAHRUNG. THE CATERPILLAR’S WONDROUS TRANSFORMATION AND NOURISHMENT BY FLOWERS

- Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung. Volume 1, 1679

Title Page Statement (translated from German) by Maria – “…..wherein by means of an entirely new invention the origin, food and development of caterpillars, worms, butterflies, moths, flies and other such little animals, including times, places and characteristics, for naturalists, artists, and gardeners, are diligently examined, briefly described, painted from nature, engraved in copper and published independently.”

- Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung. Volume 2, 1683

- She made detailed and careful observations of each insect. She collected and kept caterpillars and conducted experiments to confirm her observations.

- She documented the stage and life cycle of the caterpillar to moth or butterfly

- Maria’s offered descriptions of specific insect habitats, which led to greater overall understanding of insights and the ability to draw new insights of insect behavior

- Her description of the specific small number of plants upon which each species depends at different stages of its life cycle. She noticed that the eggs were always laid near certain plants. She noted “caterpillars which fed on one flowering plant only, would feed on that one alone, and soon died if I did not provide it for them.” She noted special life cycle details that other naturalists did not observe. She found, for example, that some caterpillars would feed on more than one plant, but some only did so if they were deprived of their favorite host plant. The plant-host relationship is so critical, in fact, that later taxonomists named species of butterflies and moths after the plants and feeding sources on which the larvae were found.

- Maria demonstrated the physical differences between male and female adults

- Maria included thorough visual information, including the wing and underwing colorations of insects with wing orientations at different angles.

- She also documented the extended proboscis of feeding insects.

- She recognized that the size of insect larvae increase day by the day if the larvae have enough food. “Some then attain their full size in several weeks: others can require up to two months”, she noted.

- Maria noted other life cycle detials, such as molting and exosckeletons, which she drew. She said, “many shed their skins completely three or four times”.

- She noted the different ways in which larvae formed their cocoons.

- She noted the environmental factors and the possible effects of climate on metamorphosis, nourishment, and numbers

- She noted details of insect locomotion

- She observed among caterpillars that if they, “have no food, they devour each other”.

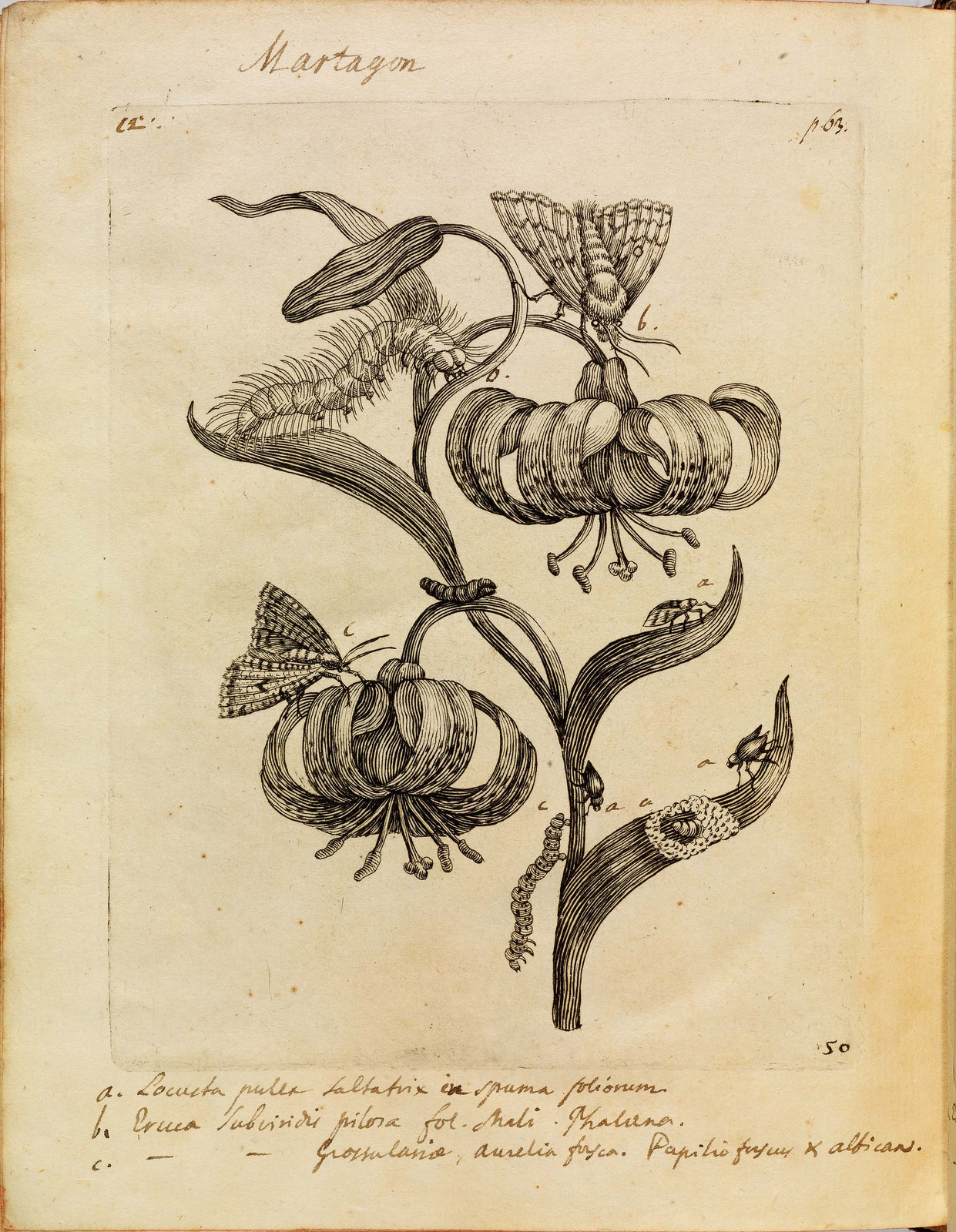

Title page of The Caterpillars’ Marvelous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, first volume, published 1679

The first plate of Caterpillars Volume 1 illustrates the life cycle of the silkworm moth. First the eggs are laid. Then the larva hatch through several molts. Merian’s made her own discovery while confirming the observations of Marcello Malpighim, Jan Swammerdam, and Francesco Redi.

Goedart, on the other hand, while a respected naturalist of the time, had not included eggs in his images of the life stages of European moths and butterflies. He believed that caterpillars were spontaneously created from water.

When Merian published her study of insects, it was still widely believed that insects spontaneously generated from dirt, mud, or water.

“Purple Tulip” (Tulipa Purpurea) 1679

Maria Sibylla Merian

Medium: Watercolor on Vellum

Image Rights: Public Domain

Metamorphosis of a Caterpillar to a Butterfly, 1679 — Maria Sibylla Merian

Dimentions: height: 19.2 cm, width: 15.5 cm

Mediums: Watercolor on Vellum

Collection: Rijksmuseum

Image Rights:Public Domain

Maria

observed insects directly,

and that alone placed her

above other sceintists of her age.

Practicing contrary to other scientists

allowed her to make

never-before noted

insights.

The Year 1681. THE LABADIST CONNECTION

The Year 1691. AMSTERDAM

In 1691 Maria moved with her daughters to Amsterdam and continued to teach them. She met with Caspar Commelin, a bookseller, historian and publisher. and Steven Blankaart, a physician, iatrochemist, and entomologist. In 1692 her husband filed and divorced her. In Amsterdam the same year, her daughter Johanna married Jakob Hendrik Herolt, a successful merchant on Surinam, originally from Bacharach. The flower painter Rachel Ruysch became Merian’s pupil.[4] Merian made a living selling her paintings and her insect collections.[5] She and her daughter Johanna sold flower pictures to art collector Agnes Block. By 1698 Maria was managing her household well on her own, on Kerkstraat Street in Amsterdam.

The Year 1699. EXPEDITION TO SOUTH AMERICA

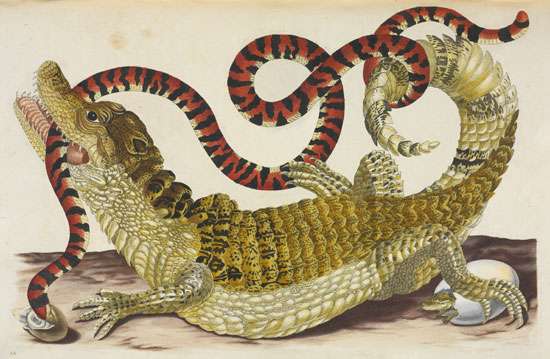

When Maria was 52, she set sail for South America with her younger daughter Dorothea as her research assistant. They settled in at Paramaribo and worked together, wandering the tropical forests in search of new insects to document and draw in detail. There were so many interesting new species to document that they did not restrict themselves to insects but also documented birds, reptiles, fruits, flowers, plants, and fish. Maria also noted the habitat, ecology, the local names and medicinal uses for different species, which would prove invaluable to later scientists. Maria used Native American names to refer to the plants, which became used in Europe for taxonomies:

“I created the first classification for all the insects which had chrysalises, the daytime butterflies and the nighttime moths. The second classification is that of the maggots, worms, flies, and bees. I retained the indigenous names of the plants, because they were still in use in America by both the locals and the Indians.”

But even in that short time, Maria had discovered a whole range of previously unknown animals and plants in Surinam. Her classification of butterflies and moths is still relevant today. Back at home, she classified her findings. She brought rare species home in her trunks: a large number of prepared exotic insects, plants, reptiles, and amphibians. She brought her scientific illustrations, research notes, and sketches of tropical beetles, plants, frogs, snakes, spiders, and iguanas. She sold specimens she had collected as a business. She criticized the Dutch planters’ treatment of natives and black slaves, back in Suriname. The excited adventure became interesting news among the scholars in Amsterdam. Visitors came from all around to view her paintings of exotic insects and plants. She wrote,

“Now that I had returned to Holland and several nature-lovers had seen my drawings, they pressured me eagerly to have them printed. They were of the opinion that this was the first and most unusual work ever painted in America.”

Maria Sibylla Merian made

many unique observations

which contributed to the fields of

entymology, botany, and zoology.

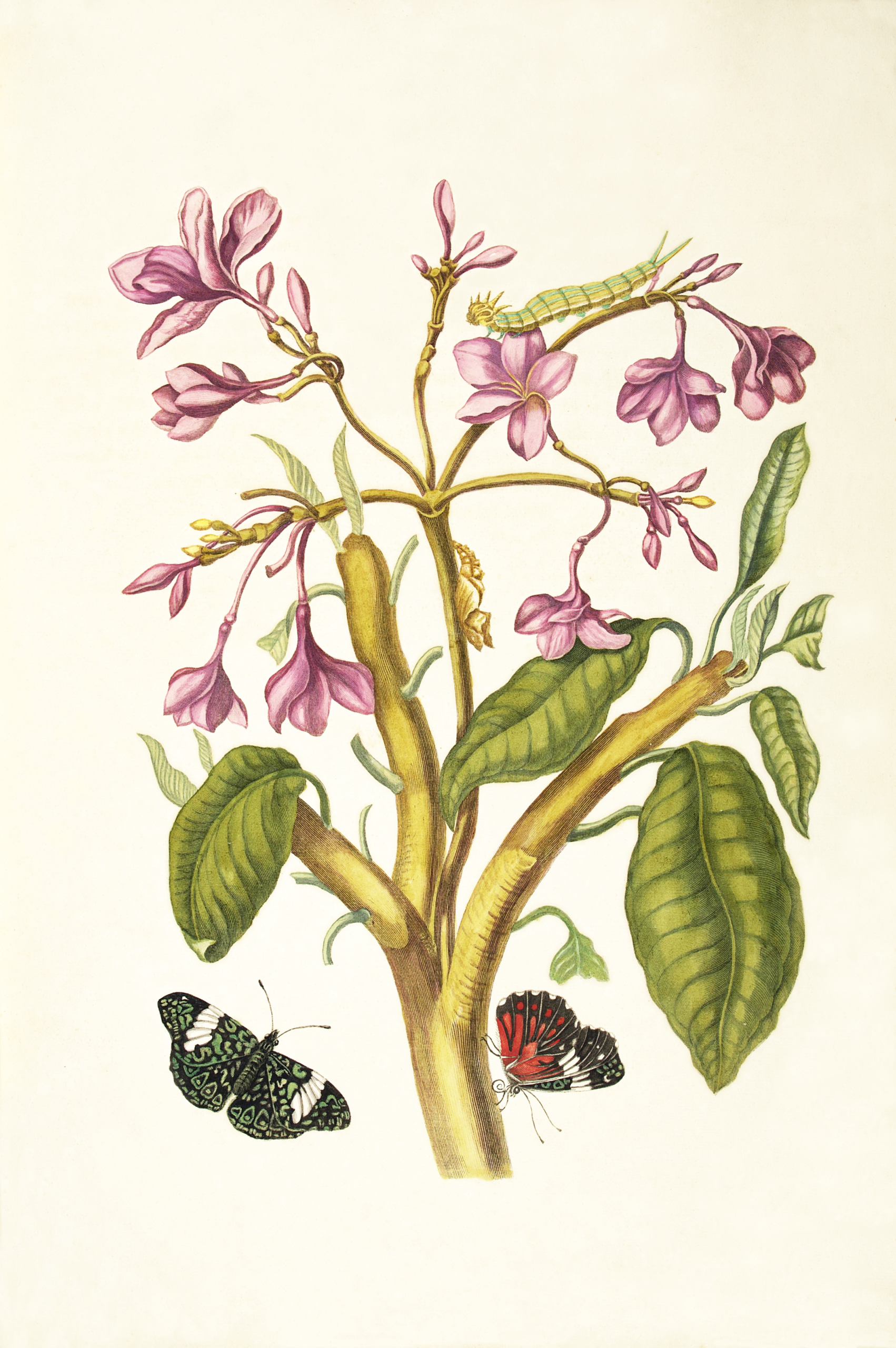

The Year 1705. METAMORPHOSIS INSECTORUM SURINAMENSIUM (Metamorphoses of Surinamese Insects)

A less expensive black and white printed edition was also prepared. Maria expressed interest in an English version to present to the Queen Anne of England, saying, “It is reasonable for a woman to make such a gift to a person of the same sex”. But this never came to be.

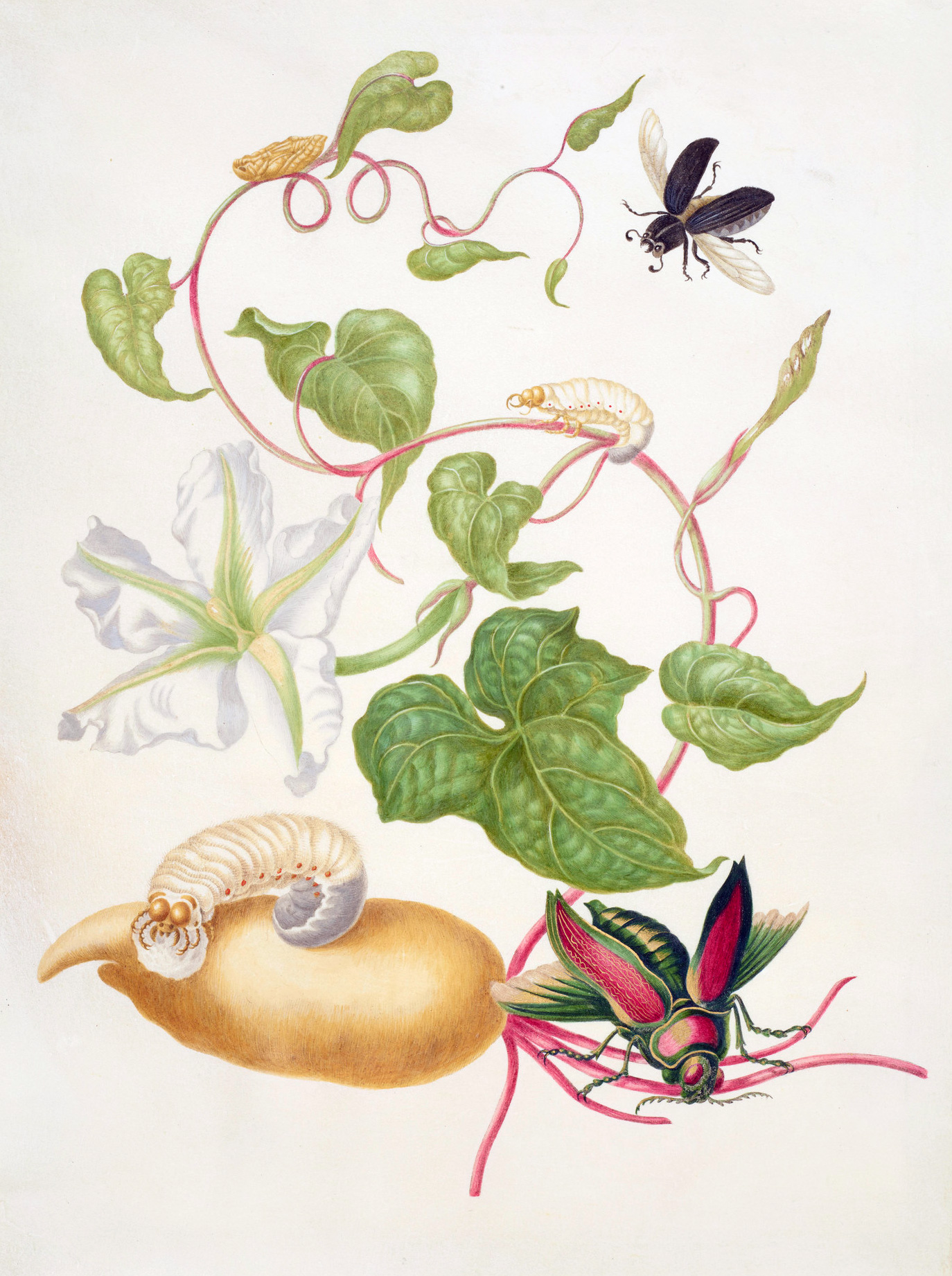

The book included 60 engravings demonstrating the different stages of Suriname insect development. In keeping with her close observation style, Maria’s drawings in Metamorphosis reveal insects on and around their host plants. Her accompanying text and included text describing each stage of development. The book was one of the first illustrated accounts of Suriname natural history.

After her death the book was reprinted in 1719, 1726 and 1730, as her notoriety expanded. It was published in German, Dutch, Latin and French.

Upon its publication her book was received with great respect and acclaim. It was noted for several accomplishments in particular:

- It was the first book with color illustrations of plants, animals, or insects from The New World, as well as natural medicines. And it would have profound influence over future naturalists. It was known not just for the documentation of metamorphoses. But also for the fire ants, which were subsequently cited and copied by other artists. The scientists Mark Catesby, René Antoine, August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof, and George Edwards all noted her accomplishments.

2. Maria writes about the struggles for life among organisms, in a manner that predates Charles Darwin and Lord Tennyson.

3. Maria documented medicinal uses of plants; among others that palm sap could be used to treat worm infections.

4. Maria made popular the pineapple, which already had growing interest in Europe, with her fantastic drawings. The pineappe featured in Hortus Malabaricus by Hendrik van Rheede, The Historia Naturalis Brasilae by Willem Piso and Georg Marggraf, and Medici Amstelodamensis by Caspar Commelin all described the pineapple. But Maria’s drawings became the most well known. She called the pineapple, “annanas”, by its local name, and described the influence of butterflies and cockroaches on pineapple crops. She wrote that the pineapple is the “most outstanding of all edible fruits,” and it is the first plate on her new book, pictured with cockroaches. One insect that Maaria did not argue for was the cockroach. Because cockroaches enjoy to eat sweet fruit, Maria complained they are devasting to all creatures around them by, “spoiling their wool, linen, food and drinks.” Merian’s drawing shows two types of cockroaches that lay their eggs in distinctly different manners.

5. There is a German spider called, “Vogelspinne”, which translates as “bird spider”. The name seems to have its origins in Maria’s engraving (below). The connection was not known until recently.

6. Maria’s Surinam butterfly drawings were so accurate that entomologists who analysed her sketches could identify 73 percent of the lepidopterans by their genus and 66 percent as exact species. Carl Linnaeus and other naturalists used her illustrations to identify over 100 new species. In naming the species Maria had discovered, Linnaeus abbreviated her name into Mer.sruin for animals from Surinam, and Mer.eur for European insects.

Other plates from Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (Metamorphoses of Surinamese Insects):

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1700. height: 32.9 cm, width: 43 cm

Medium:WatercolorInkPen

Collection:The Morgan Library and Museum

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1700

Dimentions: height: 33.6 cm, width: 24 cm

Medium: Watercolor and Gouache

Collection: Rijksmuseum

Image Rights: Public Domain

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1702—1703

Dimensions: height: 39 cm, width: 30.4 cm

Medium: Watercolor

Collection: Royal Collection

Image Rights: Public Domain

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1702—1703

Dimensions: height: 38.4 cm, width: 27.7 cm

Medium: Watercolor

Collection: Royal Collection

Image Rights: Public Domain

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1702—1703

Dimensions: height: 36.1 cm, width: 27.8 cm

Medium: Watercolor

Collection: Royal Collection

Image Rights: Public Domain

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1702—1703

Tropical White Morning Glory with two beetles, 1703 — Maria Sibylla Merian,

Dimensions: height: 37.1 cm, width: 27.5 cm

Medium: Watercolor

Collection: Royal Collection

Image Rights: Public Domain

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1705

Dimensions: height: 44.0 cm, width: 28.7 cm

Medium: Watercolor

Collection: Royal Collection

Image Rights: Public Domain

Maris is the first entomologist to reveal

the life cycle of the butterfly and moth.

The Year 1710. FLOURISING

At this point Maria began to focus her interest in live insects. When she received a specimen from James Petiver she wrote that she only cared about “the formation, propagation, and metamorphosis of creatures, how one emerges from the other, and the nature of their diet.”

Maria accepted contract work to earn extra income. In 1705 she helped to illustrate the book The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet written by Georg Eberhard Rumpf. She also earned income as a teacher, paint seller, and by preparing butterflies for commercial sale. It was just enough income to get by.

The Year 1717. DEATH

The Year 1718. ERUCARUM ORTUS

‘Erucarum Ortus, Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis’ 1717 by Maria Sibylla Merian is available online Göttinger Digitalisierungszentrum

‘Erucarum Ortus’ features some 150 plates of butterflies, caterpillars, moths and other insects together with their associated plants. The book is divided into three sections and about half of the first section of illustrations – in thisparticular copy – has been enhanced with hand-colouring. The balance of engravings below were sampled from throughout the book. The opium poppy plate was cropped back to the engraving plate margin; all others were chopped off at the page edge. I haven’t checked whether all the hand written species names on the book pages are correct or not.

MARIA’S LEGACY

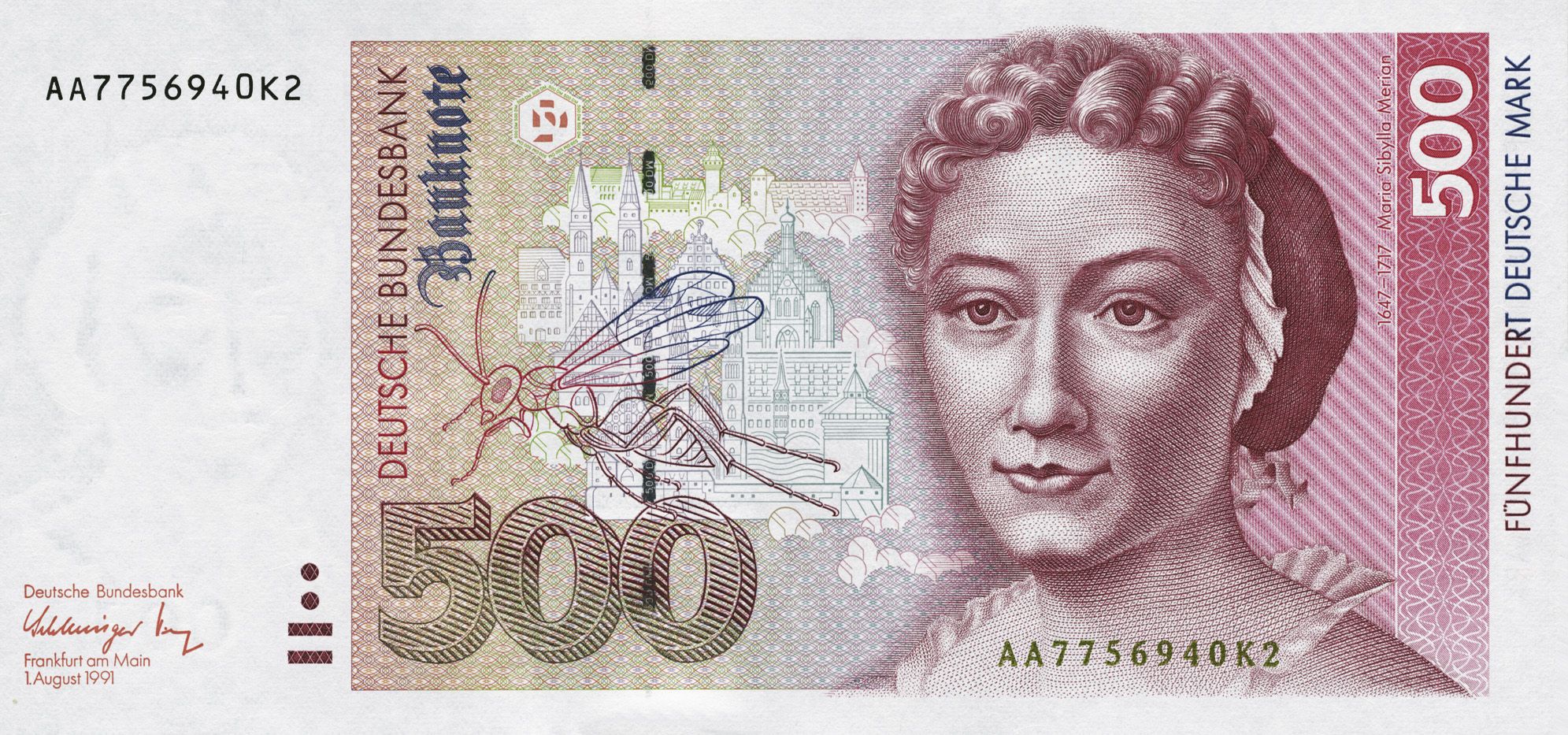

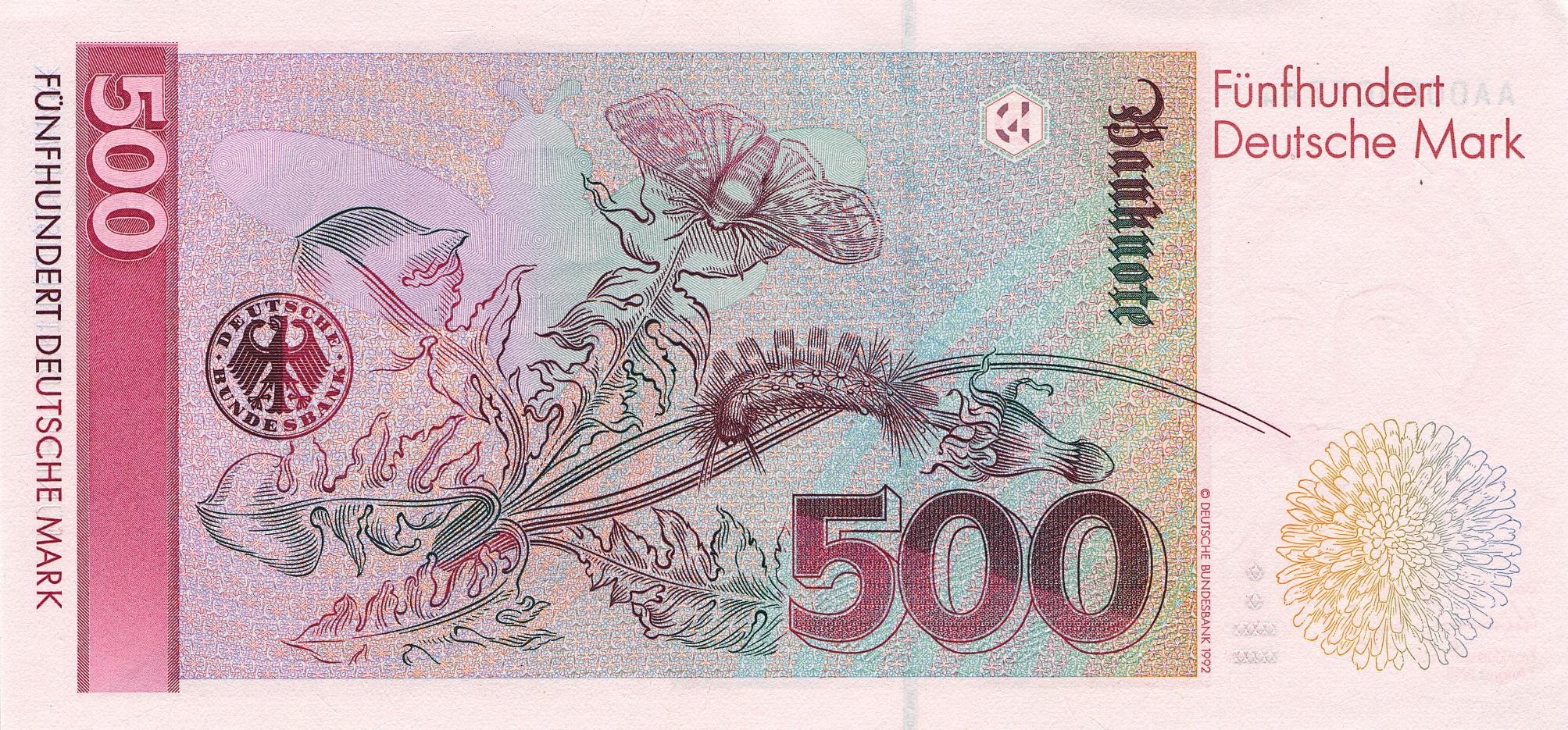

1990-2002 The 500 DM banknote bears Maria Sibylla Merian’s portrait.

Maria Sylliba Merion remains

one of the greatest contributors to

the field of entymology.

Maria’s accomplisments are celebrated in new publications of her work:

FURTHER EXPLORATION

Short films describing Maria’s life story:

Gorgeous video with closeups of Maria’s insect drawings and paintings:

Closeups of flowers, too:

ARTICLES

The Woman Who Made Science Beautiful

Marian Sibylla Merian content in this article are ill

June 7, 2018

Laura Maaske, MSc.BMC, Medical Illustrator & Medical Animator| e-Textbook Designer