A Line to my Heart: My Career and Life as a Medical Illustrator

A Line to My Heart : Life as a Medical Illustrator

Written & Painted by Laura Maaske, MSc.BMC, Medical Illustrator & Medical Animator| e-Textbook Designer

Monday, July 18, 2011

What comes to mind when you think of a medical and scientific illustrator? Is it a kind of art you admire? How do you respond to highly detailed drawings? Do the fleshy human interiors make you squeamish, which is a remark I have sometimes received from clients regarding medical images in general? Does the precision impress you? Does the stiffness offer you stillness or rigidity, something to explore? Do you love the great masters of the field: Leonardo DaVinci, Andreas Vesalius,Max Brödel, Frank H. Netter, John James Audubon?

As a student medical illustrator, I knew what I wanted to learn. I wanted to wrap my mind around the science and the drawing skills I would require in the future. I already had an undergraduate degree in zoology, and our courses in the Division of Biomedical Communications were to be shared with the medical students at the University of Toronto, so science was heavily on my mind. There were levels of basic knowledge I needed to learn and those were challenging enough. I saw the scientific method as the most reliable process for truth-seeking. It seemed to me, if I could grasp what was being taught, that the classes I enrolled in formed rational containers to hold all the knowledge I would need in my work: anatomy, physiology, pathology, embryology, histology, design, airbrush, carbon dust, pen and ink, wash, to name a few. I still adore them all.

What a remarkable world we live in that an idea like the scientific method with its meticulous observational approach and the respect for repeatable results that it nourishes, have produced such a vast body of insights. And also, how remarkable that the notion of an artistic apprenticeship and the skills it entails have created a line of hands reaching back in history: generations of artists still passing the skills down in a highly oral tradition. We live in a world with a high degree of specialization in our work, so the idea of mastering that breadth is simply not possible. But what a joy I felt to be learning in a place with others who wanted to grasp, to whatever degree possible, both science and art.

I didn’t realize then, because I had not yet discovered the nature of my personal search, that while I admired the greats in medical illustration and studied their hand-strokes for a glimpse of the genius they contained, that there might be something deeper to be reaching for in the execution of that fluid line than the enticing surface of the lovely stroked paper itself. Looking at the masters, I didn’t see what I would later identify in them as the source of inspiration. It’s what gives any artist the energy of the search: the pull from within, the questions one might be asking, or the personal exploration. That expression might begin in an awkward way, with a sense of the gentle tug that begins from one’s heart, moves to the head, and then emerges out of the fingertip. This is what the Chinese calligraphy masters suggested. It is the discovery of unity, beauty, and self. There must be other ways that artists have found. But this is the way it happened for me.

I was discovering a second wellspring of knowledge in addition to science. I was beginning to respect another empirical source: my instincts. Looking to the great artists and poets I began to see a shared language in the exploration, and a gesture pointing to some kind of truth beyond rational grasping. Poetry and art are themselves a source of truth and this can be discovered and revealed with the same attentiveness and dedication and need for honest acceptance of results that a scientist lends to the process of discovery.

Finding freedom of this kind may be inborn to some artists, but has taken me years to unveil. Even as a student, or especially then, I recognized that my arm was tight and my line did not flow luxuriously. I appealed to Professor Stephen Gilbert, a master with the pen. He suggested I draw a hundred circles a day, in the morning before class. I did this exercise, but I found myself becoming more rigid and feeling as if I had less control over my hand than ever. Even a ritual like this was not reaching me. Professor Gilbert then suggested that I begin to explore a looser style, which seemed at first a contradiction to the precision I was looking for. He was right. In my personal drawings, I had a looser style. But I found, over time, there began to be a connection between the loose sketchwork I loved to prepare in my personal work, and the tighter style required for my profession.

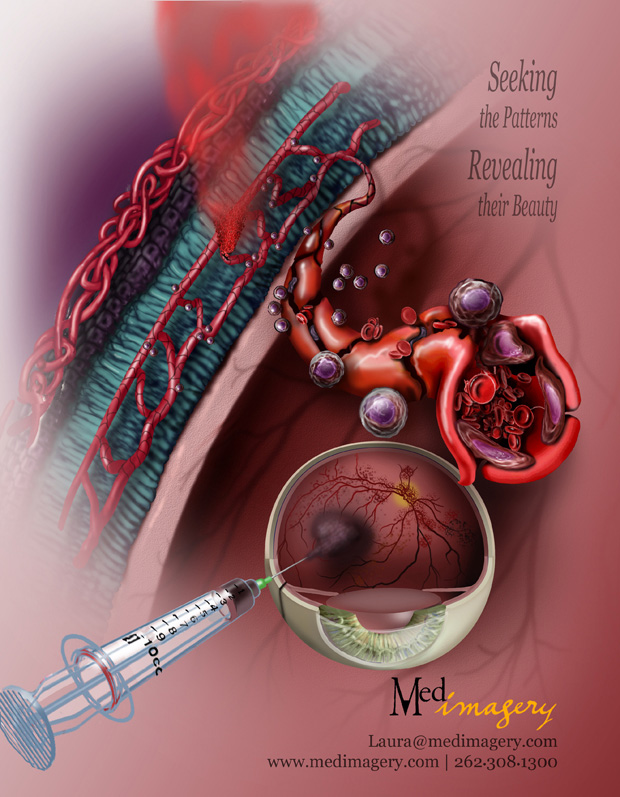

Recently, a fellow artist asked me how my own questions might come out in an everyday practice of illustration. I guess it begins with the first questions we ask as we draw: wondering about the patterning of life. Why does the branching of the tree look so much like the arterial branching patterns? What does light mean as it passes through a leaf wall and how should it look as it is passing through a cell membrane? What is light, anyway, that it behaves in such a different way from other materials I am drawing? I take these questions to my camera, which has offered an ongoing exploration and source of new insight to my depiction of the inner forms. Questions about beauty are newer to me. I wonder what makes the shape of a line beautiful. I practice making curves on paper. I wonder about these curves when I draw any form or any shape, and I ask instinctive questions about whether a line I’ve just drawn offers that beauty.

Other questions begin in a more practical place, but make me wonder about greater things. What makes a medical illustration impactful? Is there any such thing as beauty in the depiction of a disease process? How can the experience of looking at a medical illustration be made to be meaningful to a person who needs help making a health decision? How does a person turn to the outside world to help make decisions about health and medical choices? How can an illustration hold this kind of inspiration? What is the nature of the relationship of a person to the world and its ability to influence actions? As a student, I preferred quantitative research which offered the most shallow results from the greatest number of people. Now, in conducting small qualitative surveys for my illustrations and work, I find myself simply preferring this approach. It allows me to rely on my instincts as an artist, and to ask deeper questions. I’m not so concerned about universality.

In that reach from myself, and despite this technological age, there is hand-work. I ask the question that all artists ask, and maybe every person asks: can I make what’s deepest in me real in the real world?

More artwork from Laura:

See my full article at http://www.labspaces.net/blog/1411/A_Line_to_My_Heart

July 18, 2011

Laura Maaske, MSc.BMC, Medical Illustrator & Medical Animator| e-Textbook Designer | Health Communicator